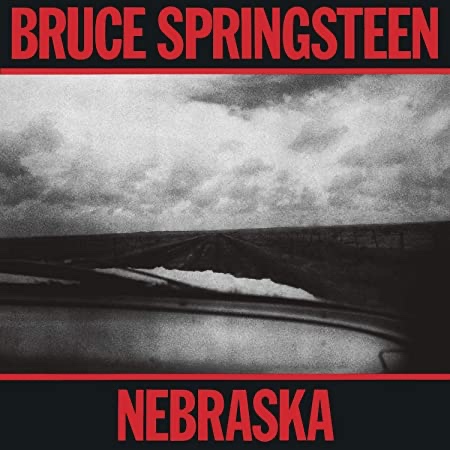

Warren Zanes (the Del Fuegos) has written Deliver Me From Nowhere (2023, Crown), a fascinating trip through Bruce Springsteen’s creative process and emotional journey of his iconic work, Nebraska (1982).

Why does this story matter? The collection of folk-gothic songs is hailed as a magnificent portrait of America, in the same vein as The Grapes of Wrath, The Great Gatsby or To Kill a Mockingbird – distinctly American stories of grit and tragedy. The writings of Flannery O’Connor are mentioned quite prominently in the story, as an influence to Springsteen and mirroring the undercurrent of flawed and grotesque characters in hard, painful situations.

While Zanes is a fellow musician, he’s an established author, educator and musical historian. With a doctorate from the University of Rochester, a musical education as a songwriter/performer, and documentarian of popular music, his talent for storytelling makes this story much more than simply an album review. Zanes peels the layers of Springsteen’s work and of the megastar of the early 1980s.

Springsteen’s star was rocketing into the stratosphere after The River, and his biggest work was just ahead: Born in the U.S.A. In between, a stark, demo-quality collection of downbeat, solo acoustic recordings – not exactly the recommended trajectory for a white-hot rockstar.

“Here’s Bruce Springsteen making a record from a kind of bottom of his own life,” Zanes added of the album. “Nebraska was muddy, it was imperfect, it wasn’t finished. All the things that you shouldn’t put out, he put out.”

While Springsteen’s career was soaring, his life was not. For a CBS Sunday Morning interview in 2023, Springsteen revisited the rental house and bedroom where he created Nebraska. “I just hit some sort of personal wall that I didn’t even know was there. It was my first real major depression where I realized ‘Oh, I gotta do something about it.’”

Springsteen’s plan was to write and demo the songs, then assemble his band in the studio to record the songs. “I had planned to just write some good songs, take it to the band, go in the studio and record it.” Then he realized the strength of the songs was amplified by the starkness of the demos. The recording studio only diluted the grip of those haunting songs.

Nebraska was the polar opposite of The River, in every way possible. After The River worldwide,yearlong tour, Zanes writes that life was different for Springsteen. Most of the money Springsteen earned from the tour and album went to help buy him out of his management contract with Mike Appel. One of the few benefits of his success was a brand new Camaro, his first new car.

Springsteen did not own his own house and needed to find himself a new rental, which he found in Colts Neck, New Jersey. His soon to be former girlfriend helped furnish it with used and discarded furniture. Not exactly the life of a rockstar.

After The River tour, Springsteen had the time to contemplate his future, but it his past that occupied his thoughts, and fears. The transient life as a musician kept him from putting down roots, and kept him worrying about money. What should have been a happy time instead brought ghosts.

“Nobody gets a do-over,” Springsteen writes in Born to Run, his autobiography. “Nobody gets to go back and there’s only one road out. Ahead, into the darkness.”

The ghosts of Nebraska were from his hometown, which he regularly visited, barely ten minutes from where he was now living. Nebraska, he wrote, was an unknowing meditation on his childhood. “Black bedtime stories,” he remembered.

Most curious is that Springsteen was undergoing some feelings of intense change and untethered sense of normalcy. Springsteen lived and breathed rock and roll, and his success, in Zanes’ interviews with Springsteen, revealed a feeling of disconnection with his fan base. A blue collar songwriter, big venues and stardom felt uneasy. Springsteen has always been deeply introspective and constantly using his own experiences as the basis for songs that tap into the restlessness and angst of finding your way in the social landscape of America youth. Nebraska would mine these feelings and the loneliness of his own youth. Again, not exactly rockstar material for a follow-up to a hugely successful album.

Some of the inspiration for Nebraska came from the 1972 film by Terrance Malick, Badlands, about Nebraska teenage killer Charles Starkweather. Somehow, Springsteen found something in Starkweather’s youth that aligned with his own difficult 1950s upbringing. Zanes talks extensively with Springsteen about those years, living with his grandparents in a crumbling house and feeling embarrassed by their circumstances and lack of parental interest in his young life.

Zanes’ writes about how watching Badlands late at night was a sort of epiphany for Springsteen’s method of songwriting: He thought in terms of images and visual storytelling. The songs were visual vignettes of words and music. Springsteen recorded his songs on a Teac four track recorder. These devices were new, the power of home recording had not hit the masses yet. Springsteen could record basic tracks of voice and guitar, and then overdub a few additional instruments, and even had his choice of a few effects. It was simplistic, but perfect for this journey. In the end, the home recordings would form the basis for the final mix.

In the studio working with the E Street Band, Springsteen felt the characters in the songs slipping away. The more they worked, the greater the distance became; Springsteen knew the power of these vignettes was in the rawness of the demos. At the same time, Springsteen had the band play some other songs that were thematically unrelated to his demos, songs that had a whole different vibe, songs that would sit for a year before being released as Born in the U.S.A. That album would establish Springsteen as one of the biggest stars on the planet, but that would have to wait.

Zanes takes us inside the “war room,” the production people trying to figure out how to release what became Nebraska. The re-recorded songs were out, Springsteen declared. They tried working with the TEAC tape, but no one was happy with the transfer to the studio equipment. Finally, they used the cassette tape that Springsteen used to copy/mix the songs for the demo.

Springsteen told Zane’s that Nebraska gave him a lot of creative freedom. He went on to say that without Nebraska, there wouldn’t have been a Born in the U.S.A. as it was released. The material was recorded at the same time; the albums were intricately connected. Springsteen would later say that Born in the U.S.A. stealthily carried the forward the undercurrents of Nebraska.

Columbia Records released and supported Nebraska, understanding it was different. Springsteen refused to tour or actively promote it, although he did also a music video to be created; it aired on this new thing called MTV.

I won’t review each song, but generally, the album is haunting and melancholy, stark and eerie, plaintive and evocative. The songs are little stories, narratives of difficult and painful times. With mainly his guitar and harmonic, occasionally a second guitar and backing vocals, the songs all sound different, which is amazing given the limited production palette. Despite the production, mixing and mastering difficulties, the sound is fuller than I had thought. Springsteen was not able to re-record the songs to match the emotion or mood of his original performances.

This was an important album in Springsteen’s life and career. Deliver Me From Nowhere is really for hardcore Springsteen fans and music historians. Zanes provides a great deal of subtext and context in telling the story, and his ability to tell a story makes this a very intriguing read.

The album:

- “Nebraska” 4:32

- “Atlantic City” 4:00

- “Mansion on the Hill” 4:08

- “Johnny 99” 3:44

- “Highway Patrolman” 5:40

- “State Trooper” 3:17

- “Used Cars” 3:11

- “Open All Night” 2:58

- “My Father’s House” 5:07

- “Reason to Believe” 4:11

Total length: 40:50

Leave a comment