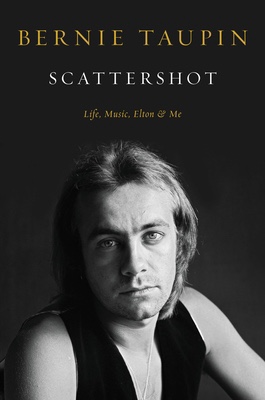

Bernie Taupin, songwriter partner of Elton John on most of his songs, has written his memoirs. Scattershot: Life, Music, Elton & Me (2023, Hachette Books), takes you inside the juicy and often excessive world of rock ‘n’ roll. But this really isn’t a sex, drugs and rock ‘n’ roll book, even though it has a steady helping of each.

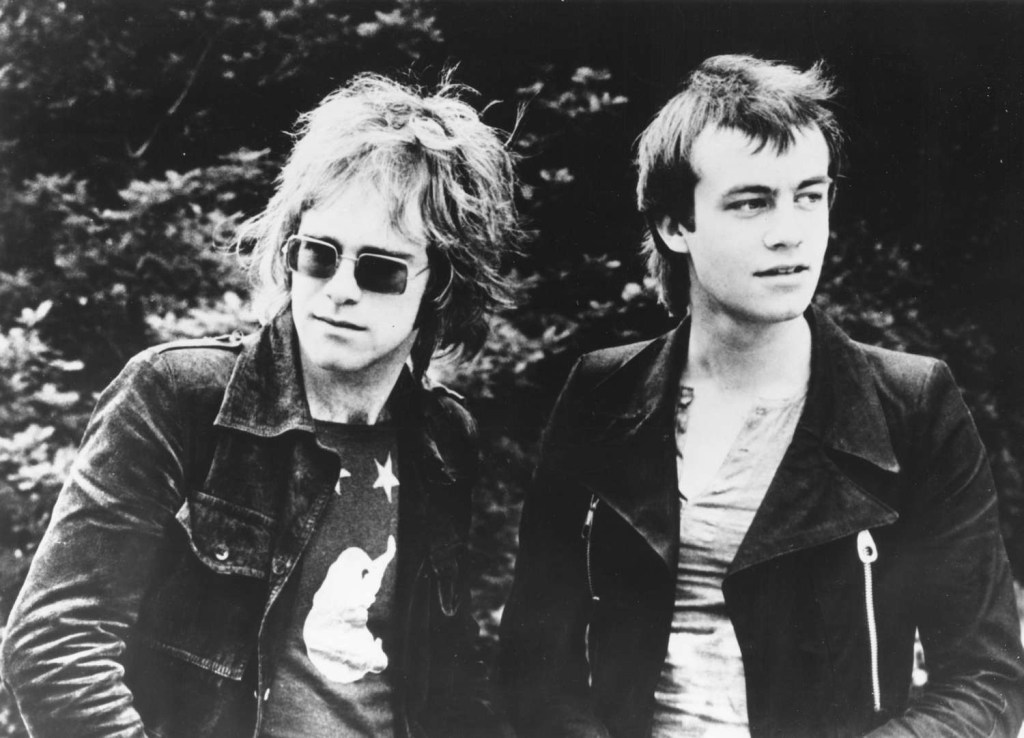

Let’s begin at the beginning. Elton John composed the music to Bernie Taupin’s lyrics. The two have been collaborators and friends for more than 50 years.

“I’m a storyteller…A lyricist? I don’t know what that means.” That’s what Taupin said to television interviewer Gayle King as he was promoting this book. He’s not a great interview, or at least he wasn’t in this case. But as this book reveals, he’s a compelling writer and storyteller.

Taupin is much more comfortable describing the circumstances, events, places and people of his life, than of himself. He has a talent for painting his history, places like L.A. and New York of the early 1970s, a world many have written about, but Taupin is able to give those places a unique telling. Just not on live television.

Bernie Taupin is an interesting story. For a young man who did not qualify for the path to college, rather to what we call blue collar work, Taupin surprised those who wrote him off, by using the power of words and his imagination, to become one of pop music’s most successful lyricists.

Taupin and Reg Dwight (pre-Elton John) both worked for low pay for music publisher Dick James, writing songs that would hopefully be sung my others. Yes, they would certainly accomplish that, once they stopped trying to craft knockoffs of middle-of-the-road pop hits, and focused on constructing their own musical ideas. James, by the way, was the publisher of the Beatles, and who would eventually sell the Lennon/McCartney catalogue out from under their feet.

On his friendship with Elton, Taupin writes:

“They say that opposites attract, and there are no one more opposites than we are. It was an army of two. Me and him against the world. From the moment we made our mark, we severed our umbilical cord and went our own way. Our devotion to each other has never wavered, and our friendship grew substantially just as our lifestyles took radically different paths.”

Taupin has a deft way of describing his life journey, and what he saw as a young man looking about the world:

“The streets of this time both in the US and the UK were ringing with raucous protest. War and government were the enemy; idealists and demagogues thrashed out their differences with bullhorns and placards. On soapboxes in the parks, pseudo-revolutionaries in their berets and Che Guevara T-shirts bellowed out flatulent manifestos while in the hallowed mahogany halls of Parliament political dogma fell on the deaf ears of England’s youth.”

The very first thing that impresses me about Taupin’s writing is his profundity and eloquent style of word play.

“My mother, because she loved him (his father), had forsaken the artistic and cultural benefits of cosmopolitan life to be his rock. I believe that swapping the gratifications of urbanity for a different aesthetic was one of the bravest things she ever did in her life. For a woman as idiosyncratic and completely in the thrall of every facet of the arts, it was a choice that could not have been made easily.”

Another early reveal is how uncomfortable Taupin was with fame, or the attention it brought. As half of the songwriting team, he was featured on albums and publicity as if he was a member of the band, which he wasn’t. In the late ‘60s and early ‘70s, it was not unusual for songwriters to be counted as members of the “team.” Think of Peter Brown, lyricist for many Cream hits, Pete Sinfield, lyricist for early King Crimson and ELP songs, and Keith Reid of Procol Harum.

In nearly four hundred pages, Taupin devotes very few to his songwriting. Here’s one example:

“On Monday morning, October 27, 1969, Sheila fried up a couple of eggs slotted in some toast and brewed three cups of tea while I wrote something called “Your Song.” I don’t think it took me more than ten minutes, but it’s eventual melodic accompaniment and release would traverse decades, becoming our signature song and, in the minds of many, our first bona fide classic.”

Taupin’s says his lyrical influences came from observing, plus the people he interacted with. Part of the reason he attended recording sessions and went on tours with Elton was to engulf the experiences and parts of the world that were outside of his bubble. He wrote about people, and he turned his own relationships into song. That’s to be expected of any writer. Surprisingly, there was one other major cultural influence: The American West. The films, the music, the landscape, cowboy life, and the spirit of the frontier. An English boy would grow up to own a horse ranch, ride in rodeos and train horses. He believes The Wild Bunch is the greatest American film. Cowboys are America’s last renegades, he says. Giddy-up!

Another quick passage on the birth of a song: “I finally completed that lyric that had sprung to mind the morning after my first traumatic night in New York. “Mona Lisas and Mad Hatters” is peppered with references to that rudimentary rough patch. It’s not about survival; it’s about understanding and coming to terms with the naked truth. My “trash can dream” did come true and ‘rose trees’ do ‘grow in New York City.’”

These are wonderful slices of a creative process responsible for some of the most evocative song lyrics in modern music. Too bad he didn’t give us more. One observation of his I found astounding, that few of his songs are traditional love songs. Taupin calls himself a storyteller, which is true. If you scan his song titles, which I did, there are lots of stories about zany characters, broken hearts and survival; but not many love stories. That’s an interesting revelation, one I didn’t expect. The song “I’m Still Standing,” which signaled Elton’s career resurgence in the early 1980s, was really about Taupin’s breakup with a girlfriend.

But he only mentions the five-year gap in his working relationship with Elton. These men were closer than brothers, what happened that pushed them apart.

While this review focuses mainly on the music, Taupin’s stories included author Graham Greene, Andy Warhol, collecting art, world travels, cocaine and alcohol fueled escapades, the Playboy mansion, American sports, and other Taupin interests. The man is certainly more than his music or a celebrity life, so beware.

Taupin does write about his occasional meeting up with John Lennon. From the Lost Weekend in L.A., to the Madison Square Garden concert appearance with Elton, it’s bittersweet. After Lennon’s death, Taupin sequestered himself for two days to write “Empty Garden” in Lennon’s memory.

Not every album was a classic, and Taupin is honest about some of the stinkers and subpar efforts. Too Low for Zero is a favorite, but Jump Up! and Leather Jackets are not fondly remembered (aside from “Empty Garden”). He also lists Caribou, Rock of the Westies and Blue Moves as inferior albums, holding Too Low for Zero, Sleeping with the Past and Made in England as much stronger efforts. He believes The Captain and the Kid got buried and never received a fair listen.

Taupin did occasionally write with others, like Alice Cooper, but mentions very little of that work. He was asked to contribute to the film Flashdance, but he said that he had no feel for the film or the music. I hadn’t remembered that Taupin co-wrote two of the 1980’s most popular and worst songs. “These Dreams,” recorded by Heart, and “We Built This City,” recorded by Starship. Absolute dreck in my opinion, but the songwriting royalties financed a great lifestyle.

“Candle in the Wind” was not originally written about Marilyn Monroe, it was conceived for Montgomery Clift, although both actors were in The Misfits, a film that Taupin really embraced. In the end, he believed Monroe was “iconically recognizable” and was “a perfect metaphor for the song’s title.” The title, Taupin borrowed from the 1960 play adapted from Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s writings about Stalin’s repression. Good call to focus on Monroe instead of Stalin.

Of his ranch outside of L.A., he wrote:

“This is where I worked and ruminated for twenty-six years, staring out at the grand vista that folded into the distance before my desk. Wide-open spaces indeed, with an equally wide-open sky, where red-tailed hawks tumbled through the clouds and glided on the thermals. It was my very own inspiration point, a ramshackle lab where the written word was king and I was simply a vessel at the mercy of my own inventions.”

One of the best stories is of Elton and Leon Russell. They made an album together, Union, and embarked on a world tour. Russell’s career had him traveling in an old bus, playing bars and roadhouses, and using a wheelchair. The album and tour proved a boost, not only to Russell’s career and resources, but reminded the public of the role he played in popular music.

Scattershot is a long and deep read, and certainly not the typical rocker memoir. Taupin is a man of profound curiosity and exploration. Elton might have the grandeur, but Bernie has the panache and understated wit.

Leave a comment