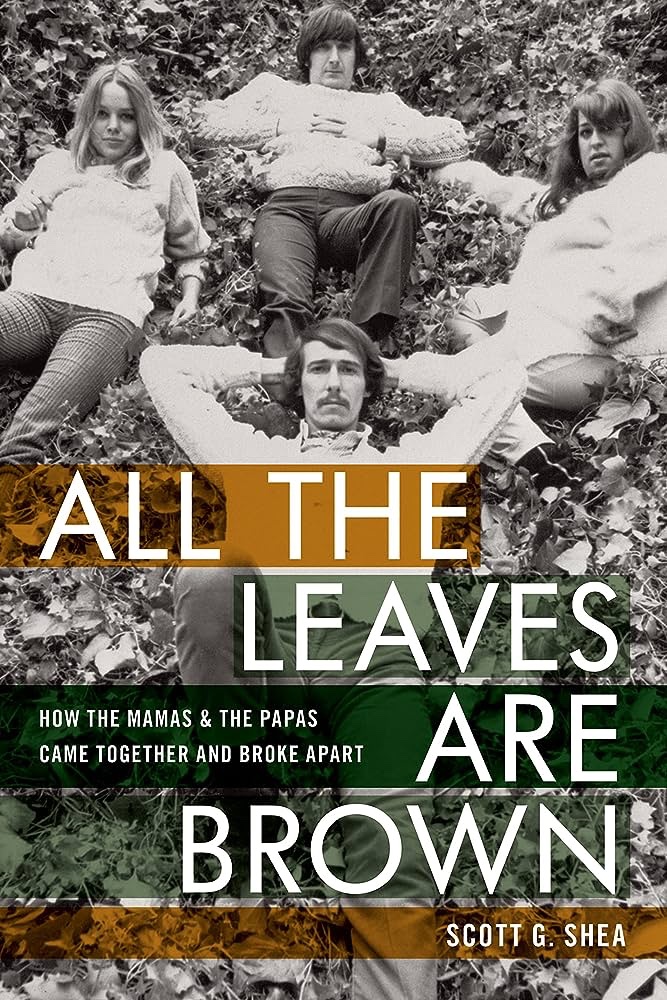

All the Leaves Are Brown: How The Mamas & The Papas Came Together and Broke Apart, by Scott G. Shea (2023, Backbeat Books), is my kind of music history. Easy to read, in-depth research, and plenty of things even a musicologist like me, did not know.

The deep-dive into John Phillip’s early life and family history is fascinating, if not very sad. While he could be charming and impressive with his talent, Phillips had an addictive, destructive personality. Shea writes, “By 1964, John Phillips was a full pledged drug addict.” Amphetamines and marijuana were his drugs of choice. He was on his second marriage, was an absentee father to two young children, and his main love was music. He had married teenager Michelle and their marriage had already weathered an affair, by her with Russ Titleman.

Denny Doherty’s story also came into focus as he broke out of the folk genre into the quickly evolving rock landscape after the Beatles landed in America. Doherty provided the tenor voice that Phillips needed, and his lead singer good looks was a bonus. Doherty also knew the talented and flamboyant Cass Elliot from the Greenwich Village folk scene.

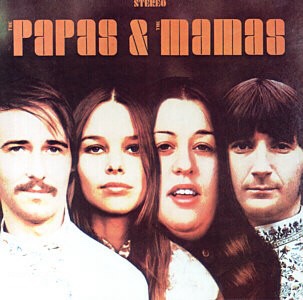

Shea paints a picture of a very diverse foursome, like ingredients in a flavorful, but combustible recipe. That’s exactly what Phillips, Phillips, Doherty and Elliot would form. Drugs, specifically LSD, the burgeoning electrification of folk, and the magical blending of their voices, were big ingredients in the formation of The Mamas and The Papas. The four first assembled on the island of St. Thomas where the Phillips and Doherty had traveled to party and form their sound. Cass Elliot arrived and had to push herself past John Phillip’s refusal to join the group. Elliot had an incredible singing voice, a gregarious personality, but lacked the desired physical features that John Phillips wanted. Eventually, her voice won out.

According to Shea, it was on St. Thomas that the romance between Michelle Phillips and Doherty began. Internal dynamics would always be a sour note for the group. Drugs, infidelity, jealousy, all sources of ignition to tear apart a musical group.

After returning from St. Thomas, John Phillips saw the sudden popularity of folk-rock and the changes going on in American culture, so he took his stockpile of songs, finally acquiesced to Elliot joining the group, and relocated from New York to L.A.

Shea’s book beautifully traces the evolution of folk music and metamorphosis into folk-rock. The Sunset Strip in L.A. was the place to be, as rock and clubs and discotheques like The Whisky A-Go-Go, Ciro’s Le Disc, Pandora’s Box and The Trip. There were other hip L.A. locations like the Troubadour where new bands broke, and record companies

The Mamas and the Papas would make the leap from folk to folk-rock as Dylan, Crosby, Stills & Nash, Simon & Garfunkel, James Taylor and others did. It’s interesting how the group became the face of what parents were afraid their children would become, yet had an abiding interest in show tunes and Tin Pan Alley classics, showing off lilting lead vocals and sweet, blended harmonies.

John Phillips had polished and added to his treasure-trove of songs through the years, waiting for a chance to record “California Dream’” and “Monday, Monday.” That finally happened as signees to Lou Adler’s Dunhill Records. Their debut album and “Monday, Monday” would both top the charts in 1966.

The Mamas and the Papas suddenly had achieved huge success, but were already imploding as their first album was climbing the charts. Marital infidelity may have the incendiary device, but the causes ran deeper. Michelle Philips exited the group, but just temporarily.

Shea focuses mostly on the Phillips and less on Doherty and Elliot. We spend a lot of time inside their marriage, without really understanding it. Michelle Phillips was eventually welcomed back into the group and as John Phillip’s wife, but it wasn’t to last.

The book gives the reader quite a lot of history, from the folk explosion of the late 1950s to the mid 1960; the period known for Dylan and The Byrds adding electric guitars and groovy grooves to folk; the emergence of a heavier, bluesy rock. Shea documents the times, not just the group. If you have a good knowledge of the period and evolution of the rock genre, you can breeze through these sections, if not, Shea provides a decent guide tour.

The Monterey International Pop Festival wasn’t John Phillips idea, but he critical to its success and was the face of the event. The first big rock event of its kind, spread over three days and featuring some of the biggest names in music. Phillips was also the face of the flower power, summer of love movement. He wrote and produced the song, “San Francisco (Be Sure to Wear Some Flowers in Your Hair)” that became a top five charting hit for Scott McKenzie in 1967.

Monterey Pop is not remembered in the same vein as Woodstock, which came later. John Phillips deserves a lot of credit for his coordination and on-the-ground direction of this event. The world saw a variety of risks artists. Among them: Canned Heat, Janis Joplin, Otis Redding, Jimi Hendrix and The Who. There were incendiary performances by Joplin and Big Brother & the Holding Company, capturing Joplin at the top of her game. The Who had yet to break in the U.S. and they opened a lot of eyes at Monterey, with their punk-like energy, before Pete Townshend smashed his guitar and Keith Moon blew up his drum set. The biggest surprise was Hendrix and his band. Incendiary was the operative word as he lit his guitar on fire as it screamed in distortion, and then he bashed the flaming axe into pieces.

Shea spends considerable time detailing Monterey Pop from inception to the final curtain; the tale is well-worth the time to read it. Whatever failings John Phillips had as a human being, his mastery of launching the Mamas and The Papas, and guiding Monterey Pop, should serve as witness to his contributions to the world of music.

The Mamas and the Papas performed at Monterey Pop, but were supposed to be working on their third studio album. John Phillips was the group’s main songwriter and he was not writing new material, in fact his energy was going into an album by protege Scott McKenzie. Each album was getting weaker, relying on covers. The group was fraying and a trip to England and the Continent compounded the disintegration.

The Mamas and The Papas had a relatively brief run, 1965-1968, four studio albums, and then briefly reuniting in 1971 for a contractually required final album. The book essentially ends with the final breakup. None of the members of the group continued the level of success once they split. That’s a different, and in many ways, a sad story.

Two things are apparent, and Shea should underlined these points. Bones Howe (The 5th Dimension, Frank Sinatra, Tom Waits) was chiefly responsible for getting The Mamas and the Papas’ first album recorded. Although not the producer, he set the template for their layered vocals. Producer Lou Alder (Carole King, Spirit, Cheech & Chong) gathered the backing musicians and oversaw production of the albums. His ear for music and ability to smooth rough waters was invaluable. Finally, the work of session musicians like Hal Blaine, Joe Obsorne, Larry Knechtel and P.J. Sloan created hooks and polished the songs.

The book is heavy on pop history, particularly the 1960s. That’s reason enough to read the book, although the focus is The Mamas and The Papas. I would call it an overview of the group, heavy on John Phillips, and light on the others, and I can’t say that I understood Phillips any better than at page one. Maybe he’s not understandable and I’ll just have to settle for knowing what the group did, just not who they were.

Leave a comment