I pride myself in knowing a lot about rock history and the 1960s L.A. music scene, but Tom Kemper’s The Monkees: Made in Hollywood (2023, Reaktion Books) taught me a thing or two. Or three.

The Monkees: Made in Hollywood, is about the made for television Monkees, a pre-fab four group of wisecracking, affable, young musicians – and how the music, publishing, promotion, touring and television arms of the entertainment industrial complex, formed a partnership to create a wild, interconnected form of entertainment.

The Monkees, the TV show, lasted just two television seasons, four albums, one film, 11 top 40 singles, a line of products, and North American Tour (1966–67), British Tour (1967), Pacific Rim Tour (1968) concert tours; but the Monkees brand made hundreds of millions of dollars over five decades.

Kemper’s book is well-researched and he lays the background for how the pop music world shifted from New York to L.A., which is important to our story. With the 1960s came rock and roll clubs, car culture, transistor radios, programmed radio station top 40 play lists, the proliferation of recording studios, record company West Coast operations, the growth of A&R operations scouting the clubs for talent, television programs focused on youth originating from L.A., and the British Invasion. The appetite for rock and roll exploded, and the entertainment industrial complex was listening, and sprang into action.

NBC was the television network that greenlit The Monkees. NBC was owned by RCA, the electronics and radio conglomerate. Screen Gems was the production studio, owned by Columbia Pictures for television production and syndication. RCA owned recording studios in Hollywood where The Monkees would do their recording. The records would be released on Colgems Records, owned by RCA and Screen Gems.

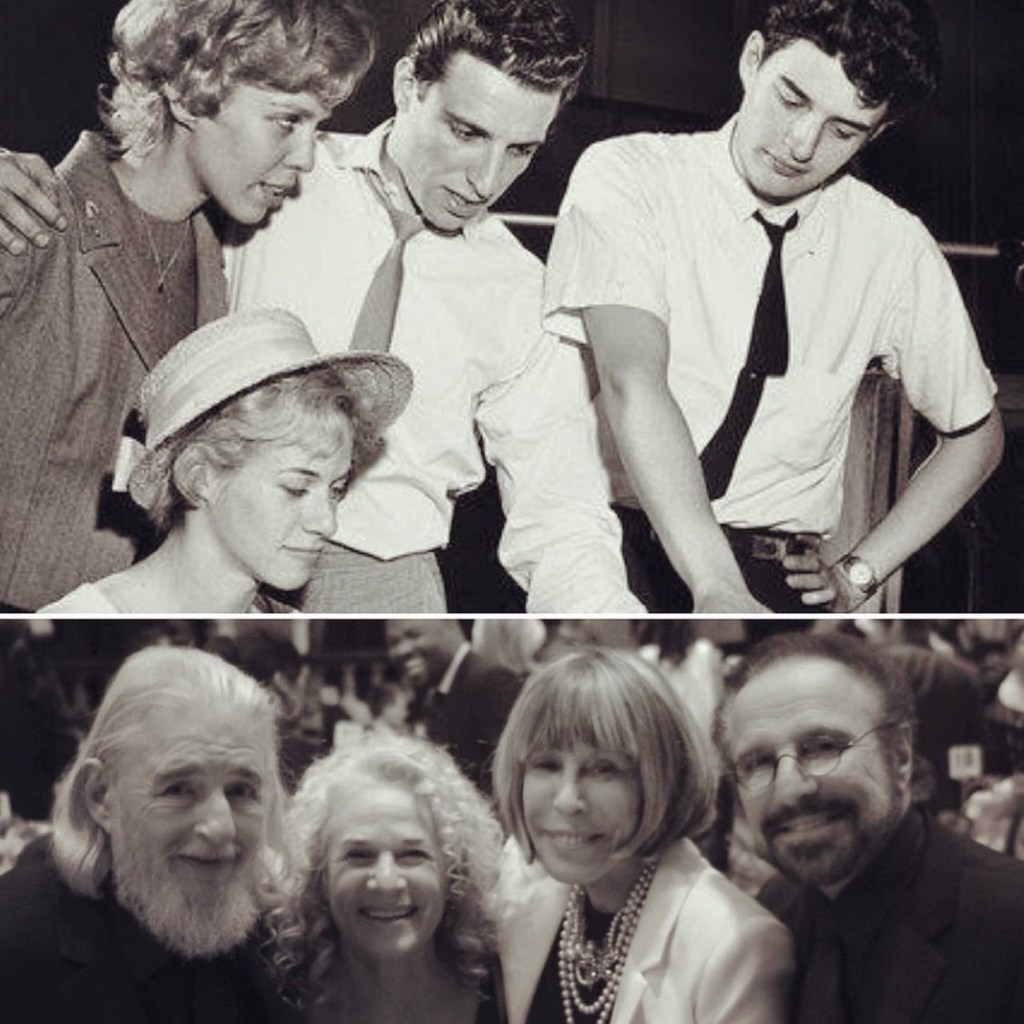

Music was a critical part of the show and required a steady stream of songs ready to record. Don Kirshner was hired to supervise the supply of songs, coordinate recording and supplying the product to the record company. Kirshner was co-owner of Aldon Publishing with offices in the Brill Building in New York, with a stable of songwriters like Gerry Goffin-Carole King, Barry Mann–Cynthia Weil and Neil Diamond, all who would provide songs for The Monkees. Kirshner was also head of Screen Gems-Columbia Music, the publisher of record for most of the songs recorded by The Monkees. Kirshner is also remembered for Don Kirshner’s Rock Concert late-night series in the 1970s.

Kirshner’s pipeline for commercial-friendly pop-rock songs were songwriters from his days with Aldon Music, who now wrote songs for Screen Gems-Columbia Music. Kemper notes that the songs were written with specific parameters, again riffing on Beatles and other top hits: use of hooks and riffs, inventive opening chords, imitating the song’s structure, mature lyrics about love gone sour as told by a detached voice.

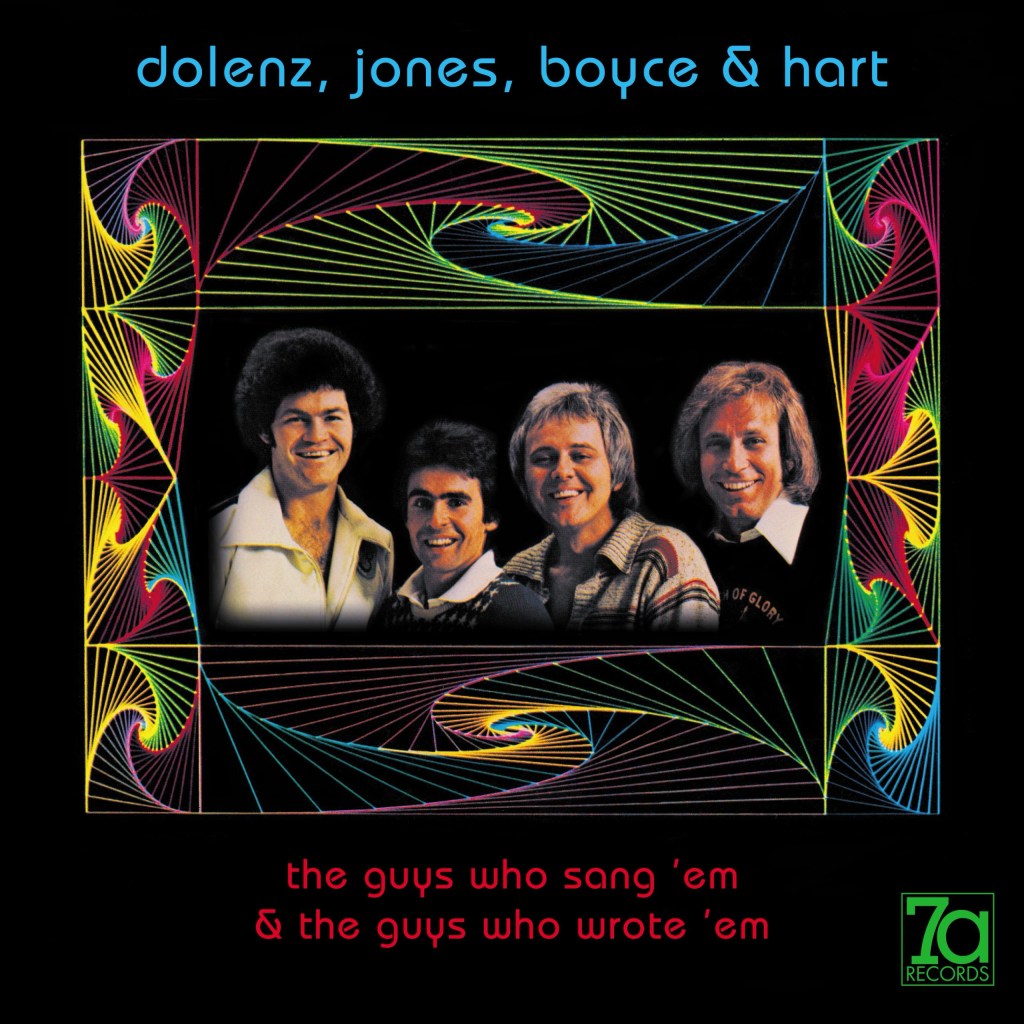

Kirshner’s team employed a handful of producers to transform demos into Monkee hits. The most successful were Tommy Boyce & Bobby Hart, songwriters and performers, who wrote and produced numerous chart hits for The Monkees. There was a competitiveness among the songwriters to top the recent hit and to top themselves. Kirshner not only used songs from his in-house writers, considered material submitted from outside. This made the competition for singles especially fierce.

The idea for The Monkees TV show was developed by Bob Rafelson and Bert Schneider, who formed a company, Raybert to produce the show with Screen Gems. Rafelson and Schneider hired Paul Mazurski and Larry Tucker to write the pilot for the series, as producers Rafelson and Schneider moved on to cast the roles for the show. Rafelson and Schneider would fund Easy Rider and make a ton of money. Rafelson and Mazurski would carve out successful carers as film directors.

The story of picking the four Monkees has become showbiz folklore. Lots of young musicians and wannabe stars were interested in grabbing one of these television roles. The club scene in L.A. was a prime recruiting target.

“The Whisky A-Go-Go got go-going because Ben Franks-types transformed the Sunset Strip, the boulevard hosting all these clubs, into a teenager hub, a center for rock and roll nightlife,” Kemper writes.

I’d never heard of Ben Franks-types, which was important in the recruitment and selection process for The Monkees television show. Ben Franks was a hipster-cool drinking establishment in L.A. The television show producers were keen on some specific qualities for their prospective actors. The trade paper ad even listed “Ben Franks-types”, which would translate into Beatlesque behavior and attitudes. It takes very little analysis to see the blueprint for the characters, scripts and music.

The Beatles seemed to invent the “put on” pop, they certainly made it commercial in a decade where Andy Warhol popularized consumer art. Kemper makes the point that the Beatles opened the door to make money from mockery. I believe that the dry, satirical, anti-establishment humor was really Rat Pack humor for teenagers.

To make that happen, the show needed more than cute, silly young men and good tunes. The show needed an unconventional style. Raybert outlined the “look” they sought and handed it over to Tucker and Mazurski for the pilot. Each episode would follow the template. Unconventional is what they got. Again, the Beatles’ film were a model, but Raybert had in mind something beyond that. Kemper describes how the show would inject the French New Wave style of filmmaking into the writing and direction. Jump-cut editing, camera speed, breaking character, title cards, handheld photography, the use of neorealism to convey skips in time of the mixture of fantasy and reality – all kinds of tricks, gadgets and devices to give the show a hyper-comedic flow, a blending of the campy Batman TV series and the Marx Brothers in a rock and roll cocktail shaker.

The Monkees were a creation for television, something that hadn’t been done before. At the end of season one, the facade was already cracking. The four Monkees wanted to be real Monkees, write their songs, play their instruments and actually entertain in the real world. In a power struggle, the pre-fab four own more control. Mike Nesmith was already a decent songwriter and handled a guitar. Peter Tork played several instruments. Mickey Dolenz was adequate to play drums in concert, but he wasn’t Earl Palmer or Hal Blaine. Davy Jones sang, as did Mickey. Mike sang lead on his own songs and Peter contributed background vocals. Still, the music arm of the production provided a good share of the songs, but the boys got a freer hand to contribute songs.

Season two was different. Not as original, not as funny, the boys were more grown up. The music was still good, a bit less pop and more rock. The “mop-tops” were more hippyish, as the show had clearly changed. The albums would feature the lads playing more of the instrument, but once they won the right to contribute more to the albums, they knew when to use songs from the stable of writers and studio musicians. The first two albums arrived during the first season, the second two during season two, and the rest of their albums following the cancellation of the TV show.

Attempts to remain hip failed. Their feature film, Head, came out after the TV show was canceled and failed to include songs that echoed their earlier success. The Monkees were formed at certain time to reflect a certain time. Evolving from that was always going to be an issue. The system, the entertainment industrial complex, the behemoth that had built them, also ratcheted up the bar that The Monkees by themselves could not match. In a sense, they were victims of their own success.

“The Monkees: Made in Hollywood is a groovy read.” – Ben Franks

Leave a comment