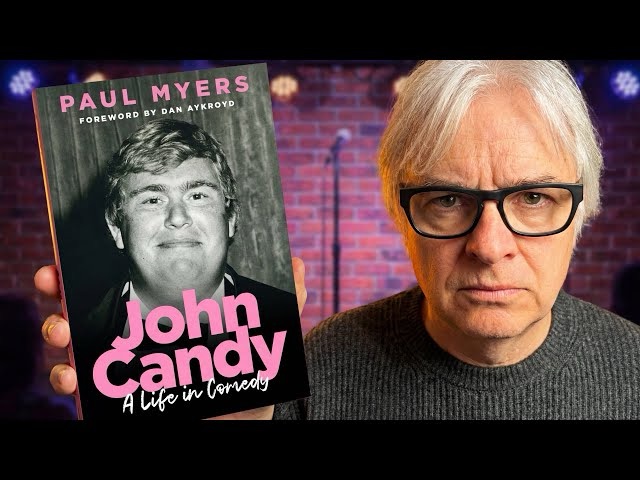

“My anger was all over the place and it came through hard and fast,” Michael Richards said recently in an interview with People magazine. The anger he’s referring to was a meltdown he had onstage at the Laugh Factory, where he made racial comments at hecklers. Captured on a phone, it was shared around the world. Instead of being known as Kramer, he was the guy shouting the N-word to members of his audience.

That night, 16 years ago, seemingly derailed his career and sent him into analysis. Richards, a very private man by nature, has been mainly out of the public eye since, but recently released his memoirs, Entrances and Exits, (Permuted Press, 2024).

Jerry Seinfeld writes the book’s forward, and lays the foundation for the self-examination of his longtime friend. Seinfeld was there during those 16 years.

“I’m not looking for a comeback,” Richards told People. He wants to understand the anger, certainly the caustic reaction that happened that night, but also the source of the pain or doubt, that he carried with him. How did one outburst crush not only his success, but his self image? Life is a series of entrances and exits, hence the book’s title.

Entrances and Exits begins with what most readers are probably looking for – the creation of Seinfeld and the character, Kramer (originally called Kessler). This was a major entrance for Richards, a defining one, but just one on his long journey.

A dozen things I didn’t know about Michael Richards:

- Hired with Ed Begley, Jr. to perform comedy between musical acts at the Troubadour in West Hollywood.

- Drafted into the Army and sent to Europe instead of Vietnam.

- In charge of a roadshow acting troupe in Germany and assumed the role of a colonel, at age twenty-one.

- Early jobs included studying to be Montessori certified teacher and a school bus driver.

- Almost aborted by his mother.

- Who was his father? And where did the name come from? I’m not telling.

- Kessler had a dog in the pilot; Kramer does not. “So, I’ll be the dog,” he says.

- The Seinfeld Chronicles is shortened to Seinfeld, and the pilot is picked up for a four-episode first season. Only four episodes?

- Season two: thirteen episodes. Not the usual 22 or 24. NBC was committed shy.

- Richards used help from actress Joanne Linville of Stella Adler’s studio to help flesh-out Kramer’s backstory.

- Richards picked out Kramer’s wardrobe and footwear himself from vintage clothing stores, and wore it during production meetings to get into character.

- An admirer of comedian Red Skeleton, he purchased Skelton’s entire 3,000 book collection upon his death.

- Monk was written for him; he declined because of not wanting to play another complicated character so close to the Seinfeld series. Regretful career move.

I found the book largely readable, but a few parts obtuse and made me wonder not sure what to make of the amount of detail. For example, his adventure with the Army acting troupe: where was he going with that, and why so much about Howard? He was an interesting character, but Howard wasn’t really an influence or player in Richards’ life later. A life lesson? I could have missed the point.

The book gets better, especially the stories of co-starring on Fridays, appearing on The Tonight Show, Miami Vice, and the unsuccessful TV pilots he made. The best stories are of the many episodes of Seinfeld he writes about. These are some of the best Kramer moments. Kramer, although loosely based on a real person that Larry David knew, was a character largely built by Richards. He developed Kramer’s backstory, created the look, wardrobe and mannerisms of the character. Richards made a habit of becoming the character on the set by dressing in his clothes.

“Most of the characters I conjure up don’t want to be there, just like me. They’re angry and rowdy.”

Richards, a self described introvert, was playing an extrovert. After the taping of episodes, the other actors went out together to relax. Richards went home and could be found at the bottom of his swimming pool in his scuba gear. That’s how Michael Richards recharged: communing with nature, reading literature, spirituality.

I wish Richards had talked more about a few of his jobs, like playing Stanley Spedowski in UHF with Weird Al, or the struggling actor in the film Trial and Error. Barely a mention of either. Disappointing.

After Seinfeld ended, Richards was not in a good place. He didn’t have an agent or a manager, and he made the mistake of agreeing to do a television show that never gelled and was canceled after eight episodes. The experience pushed him away from acting and he largely withdrew from public life.

After a few years, Richards wanted to return to standup comedy. He started slowly, playing unannounced, short sets at comedy clubs. The Laugh Factory was one of those clubs. You can read the dynamics of that night, the perfect storm of events that led to his inappropriate reaction.

After finishing the book, two things stay with me about Richards. First, Richards is known by the silly, bizarre characters he plays, not the person underneath. He hides Michael Richards from the world. He shuns publicity unless it is done in character. Few people know the kind, compassionate, highly intelligent person under the bizarro facade. This made his fall harder for people to understand; they didn’t know Richards without the character.

“This actor can play so close to himself brilliantly. How do I play close to myself? I have no self to rely upon? This makes me nervous when I’m outside of character or outside of a persona, the mask that I wear. It’s like I don’t have a Michael Richards to play? I don’t know who I am?”

Second, Richards made the mistake of not employing the right people to guide and advise him. Richards wasn’t prepared for the end of Seinfeld. He’s a loner, and underestimated the difficulty of developing projects and being in control of them, rather than being controlled by them. His failed TV series is a perfect example, it started as one thing and evolved into something he despised. Later, he needed help grooming his return to standup comedy, and the failure to do so played a crucial part in events at the Laugh Factory. That’s not an excuse, just a thread in a bigger need to discover himself.

I’m tempted to feel sad as I finish this book. That’s not the purpose of the book, to feel sorry for Michael Richards. He has lived a successful life, despite given how it started out, and for an event that redefined how many now feel about him as a person. Richards lifts the curtain to let us see the man beneath the makeup, something that seemed as enlightening to him as it is for the reader.

4.2/5

Leave a comment