Who was Duane Thomas? A talented football player, drafted in the first round of the 1970 draft by the Dallas Cowboys, and a workhorse in their Super Bowl winning 1971 season. He had tremendous ability, that was never in question, but he feuded with Cowboys front office and coaches and was traded. He moved on to other teams, and other leagues, but never achieved the success he had in Dallas. It certainly begs the question: Was his heart not in the game, did the business of football derail him, or was he searching for something not on a football field. It’s actually not as simple as that.

Thomas died, August 5, 2024, at age 77. The mystery of Duane Thomas has been explored before, but after 50 years, he’s really a footnote in football history. Thomas was an enigma, and maybe we will never figure it out.

If you saw Thomas run with a football it was a beautiful sight to behold. He had speed, fluid moves and a deceptive stride. He was drafted the year after the Cowboys chose another running back Calvin Hill, in first round. Thomas joined a backfield that included Hill, fullback Walt Garrison and halfback Dan Reeves. Teams ran the football back then and threw passes more selectively. The old saying, you can never have enough good running backs, was gospel then.

Thomas made his mark in this crowded backfield as Landry used all of his backs. At the end of his 1970 rookie season, he asked that his three-year contract be renegotiated, in light of his helping get Dallas to its first Super Bowl, but the Cowboys management refused. His 1971 salary was $20,000 and he was not even the highest paid second year player on the team.

The Cowboys returned to the Super Bowl in 1971, this time to win. Thomas felt he was the MVP of the game and suspected the Cowboys intervened in the selection, which was quarterback Roger Staubach, who had an average, but not a spectacular performance in the win. Unhappy, Thomas reportedly called general manager Tex Schramm “sick, demented and totally dishonest”, personnel director Gil Brandt “a liar”and coach Tom Landry “a plastic man.” Thomas had played the entire season not talking to the team, media or his teammates, except for that remark.

Thomas was traded to the New England Patriots, a transaction voided by NFL Commissioner Pete Rozell. Instead, Thomas was shipped to the San Diego Chargers, where he was suspended and didn’t play during the 1972 season. Traded to the Washington Redskins, he spent two underwhelming seasons before being released at the end of the 1974 season. He would play part of a season in the World Football League. After that he tried to return to the Cowboys, but was waived; signed to play in Canada, but was released; and attempted to make the Green Bay Packers in 1979, but was cut. That was it for football.

“We all come with idiosyncrasies and dysfunctions and prejudices, but we unite on the basis of what we had in common,” Thomas told Dave Barron of the Houston Chronicle. “That commonality was the Dallas Cowboys.”

Thomas said he was always at peace playing football, it was focusing on a common goal and working to achieve it. That sounds odd, since Thomas soon refused to talk with his teammates, which fed his reputation as angry and disruptive to the team.

“Duane Thomas skewed to the more militant images of the day but, unfortunately, he never had a movement behind him,” said Harry Edwards professor emeritus at the University of California at Berkeley. Edwards said that today’s players owe Thomas a debt because of his fight for economic parity and just compensation.

Thomas was angry, but his anger was directed at the system that controlled his contract, where he played, and what he felt was fed to the media. The Cowboys were a better, more competitive team starting in 1970 and Thomas was part of that. For the Cowboys to refuse to give Thomas a few thousand dollars wasn’t the issue; the Cowboys were extremely profitable; the issue was their denial to renegotiate and to keep control of player contracts. The NFLPA was just beginning to assert power in favor of player benefits and rights, however, the owners held most of the power, and the Cowboys had no obligation to renegotiate a player contract, even though the rookie contracts were tilted in favor of the teams. Twenty thousand dollars is pocket change for NFL players today, but for someone with a family to support, like Thomas, that was rent and food. Beyond that, it was pride.

I’m not going to pretend to know Thomas’s feelings or views at the time, or how he felt the media was unfair.

Players who don’t fit in, question the system, or bend to team expectations, have experienced career problems. In those days, owners, and by fiat, successful head coaches, held the cards on players’ careers. Talent was often enough, but not always. Look up the names Cookie Gilchrist and Joe Don Looney.

Gary Cartwright of Texas Monthly, wrote an outstanding piece about Thomas’s life, from his unsettled childhood, becoming a father at a young age, and proving himself in a system with a history of undervaluing and disrespecting Black athletes. Cartwright’s article goes deeper than just implying that Thomas had a chip on his shoulder and was playing the race card. Thomas didn’t have an easy relationship with Black players either, mentioning an issue with teammate Jethro Pugh and former NFL great Jim Brown.

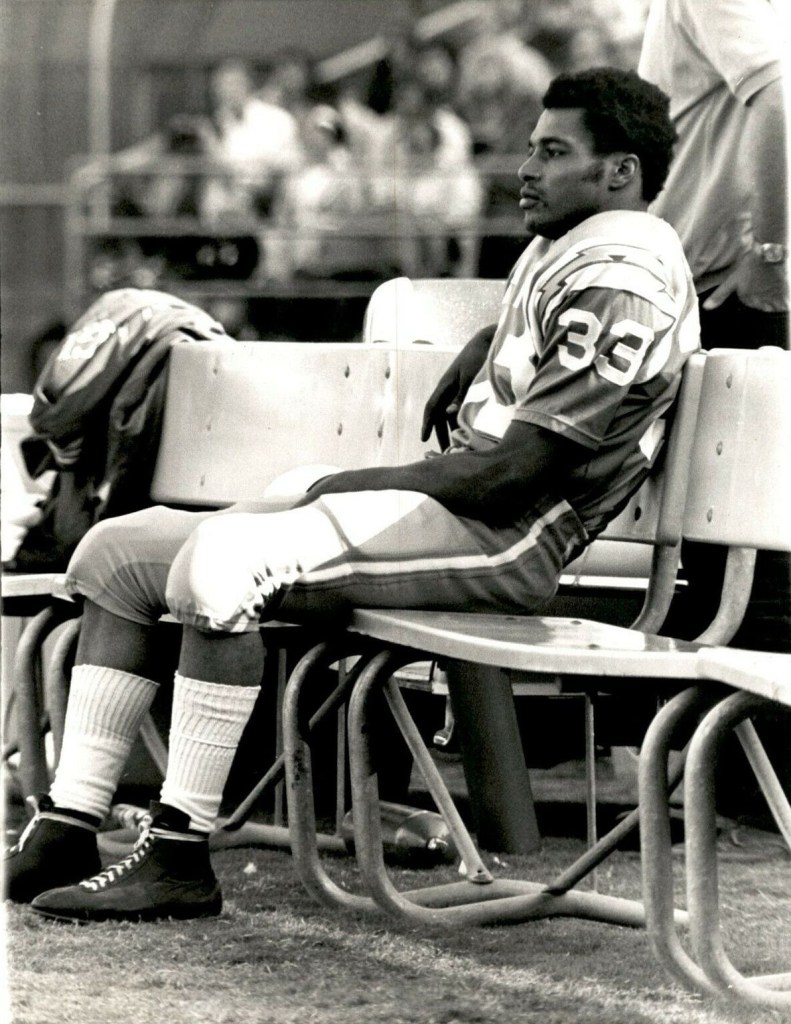

When Thomas was traded to the Chargers, Thomas immediately ran into a problem with the team and was suspended. He was brought back to the active roster, but the team made the decision to put him on the restricted list, which essentially put him on the shelf. Head coach Harland Svare knew Thomas wasn’t in the frame of mind to play football. “At this point,” he concluded, “our prime concern is to the human being.” The media, fans and players probably thought otherwise, but you have to hand it to the Chargers, who gave up a lot in the trade for Thomas, to allow him time away from the spotlight. Credit Svare, who took heat for the perception of coddling Thomas.

In an anticipated game against the Cowboys, in a nationally televised game, Thomas dressed to play, but sat by himself on the bench during the game. What was advertised as a must-see event, wasn’t.

Chargers owner Gene Klein had signed off on the trade and even a new contract for Thomas. Both Klein and Svare were patient, but clearly disappointed when Thomas’ behavior did not improve. “He’s like a kid who ran away from home,” Klein said at the time. “He wants to come back but he doesn’t know how to get into the house.”

Cartwright’s article on Thomas is fascinating, though it lays out more questions than answers. Thomas’s troubles started long before the Cowboys, fame and public expectations only dialed up the internal pressures he felt.

Years later, Thomas and Landry were known to have talked and shook hands. Early on, Landry was more perplexed by Duane Thomas than angry. He was quoted as being disappointed that he couldn’t reach Thomas or to understand the foundation for his behavior. Thomas wasn’t the first player, or last, to befuddle and test the Hall of Fame coach. The times were changing and athletes, particularly Black athletes, were challenging the system and the authority they were expected to embrace. For the next five decades, that battle was fought on sports fields and courts across every sport.

Thomas wasn’t a crusader like Muhammad Ali, Curt Flood, John Carlos, Jim Brown, Colin Kapernick and others. He didn’t carry the world on his back like Harry Edwards said, but Thomas was viewed through the same lens and painted with the same brush. His needs and complaints were no less important, yet they were personal and known (but maybe not understood) only by Thomas.

Rest in peace, Duane Thomas.

Leave a comment