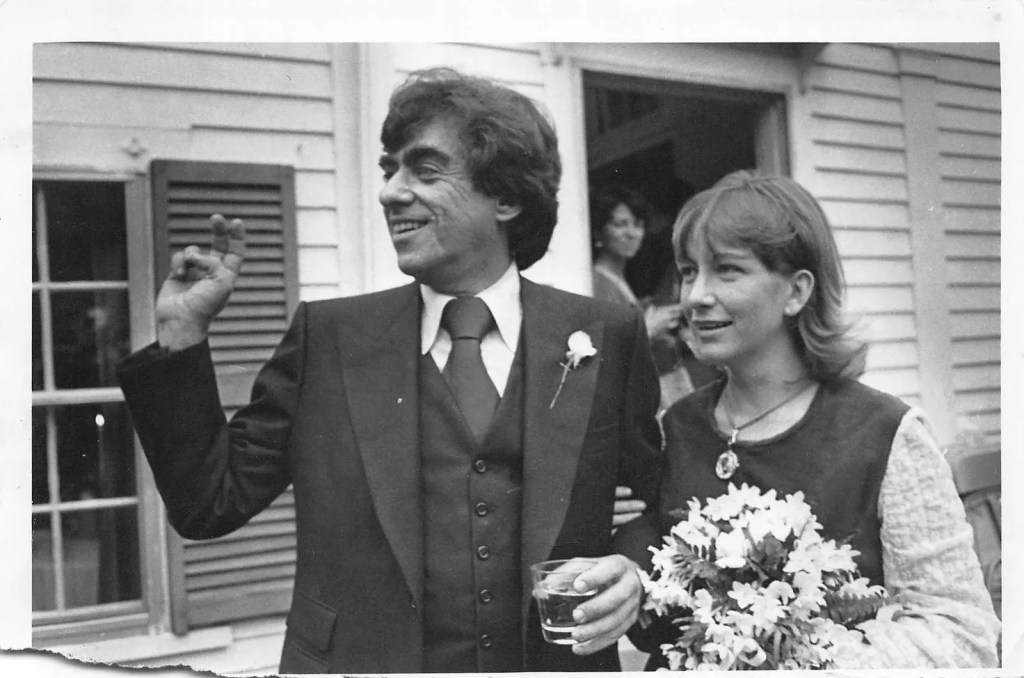

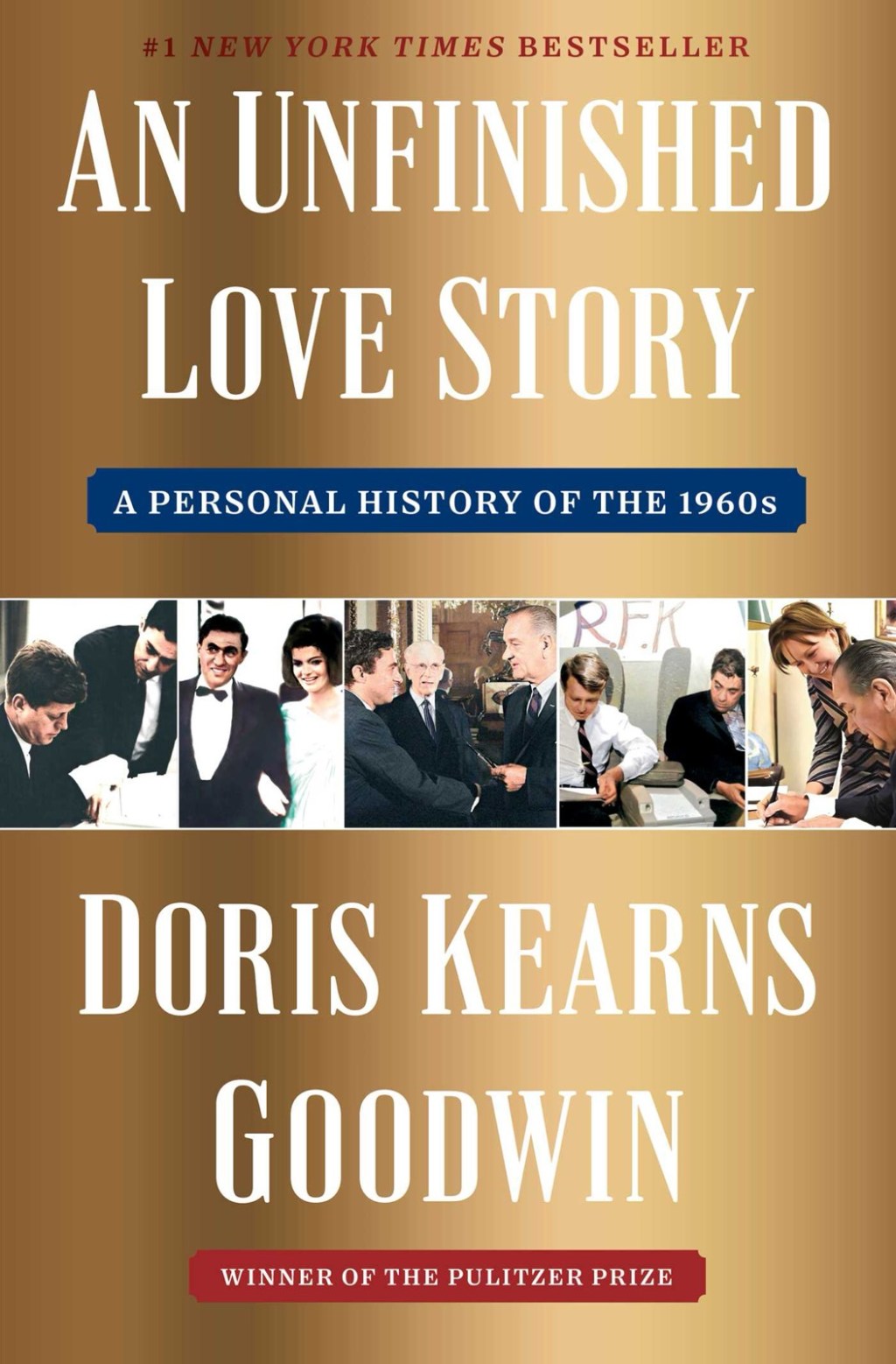

Pulitzer Prize author and historian Doris Kearns Goodwin and husband Richard Goodwin enjoyed more than forty years together, sharing a life of writing, politics, and American history. Both worked in the White House, though not at the same time, and both worked for Lyndon Johnson. Together, they were witness to and participants in the history of the 1960s, which forms the basis of An Unfinished Love Story (Simon & Schuster, 2024).

I knew of Doris Kearns Goodwin, author of one of the finest books on leadership and Abraham Lincoln, I greatly respect her as a voice of history. Her incredible book, Team of Rivals, should be required reading, not only is it important history, it’s a lesson to anyone considering asking voters to elect them to public office.

Richard Goodwin was a pack rat, he apparently saved everything from his long career in and out government and politics. He was not only a witness to history, he helped write it. Goodwin was a speechwriter and confident to Senator and the President John F. Kennedy, President Lyndon Johnson, presidential candidates Robert F. Kennedy and Eugene McCarthy. He wrote the words these men said, but also shaped programs and initiatives that became law.

Doris Kearns began working as a Fellow out of college in the White House for Lyndon Johnson, after Goodwin had left. She would serve as Johnson’s assistant after he left office. Kearns and Goodwin would later marry, and years later would unearth the many boxes Goodwin had filled with his work and mementos from the 1960s.

The book is a diary and reflections on events and memories, of one of the most important periods in American history. Many books take through history, but An Unfinished Love Story is a guided tour.

In the late 1950s, television quiz shows came under fire for fixing the results. Goodwin worked as a Congressional lawyer at the time. Kearns writes, “I hadn’t realized, however, that Dick had initiated the federal investigation that ultimately unearthed the quiz show scandal.”

Another event involved the selection of Sen. Lyndon Johnson as JFK’s running mate in 1960. As Goodwin’s notes tell, Kennedy had second thoughts and wanted Johnson to withdraw; but Johnson declined. That’s a bit of history that I didn’t know. The book has many of those footnotes to history.

Goodwin was also involved in the famous “Daisy Girl” television ad that linked Barry Goldwater with the threat of nuclear war in the 1964 Presidential election. “‘We must either love each other,’ says the voice of Lyndon Johnson, ‘or we must die’ A narrator’s neutral voice has the all-important last word: ‘Vote for President Johnson on November 3. The stakes are too high for you to stay home.’” That ad was criticized for the fear it produced, but it was as highly effective as the power of television was realized.

Goodwin was deep in Johnson’s Great Society legislation. He witnessed Head Start, student loans, scholarships, and the Work-Study Program, that opened the door to millions of first-generation students to attend college. The origins to clean water and anti-pollution legislation, Medicare and Medicaid, the end to segregated, the Civil Rights Act, the Voting Rights Act and immigration reform ending a discriminatory quota system.

Of the various White House players, Goodwin was closest to RFK, and the defining issue was Vietnam. Goodwin would leave the Johnson White House due to differing views, that he expressed in an op-ed newspaper feature criticizing Johnson, who was livid over the piece. “It’s like being bitten by your own dog,” Johnson remarked.

Goodwin would go on to help Sen. Eugene McCarthy’s campaign in 1968. He would leave McCarthy for RFK’s campaign, then return after Kennedy’s death. Kearns describes Goodwin as playing “multiple roles in both primaries and presidential campaigns: general strategist, speechwriter, debate coach, radio and television advertising consultant,” in many political campaigns.

As Johnson’s presidency wound-down, he made a request of Kearns. “To work with a small team on his memoir. He also wanted my assistance with plans for his presidential library and the LBJ School of Public Affairs at the University of Texas at Austin.”

Through Kearn’s eyes, we see a unique side of Johnson. “As time went on, the vulnerability he showed during the unrolling of his life reflected the trust we had established. Little did I know that these conversations were a gift he was giving to me, one that was quickened by his conviction that he didn’t have long to live.”

Kearns developed a close relationship with Lady Bird Johnson. She writes that as declining health robbed the former First Lady of her ability to speak, that didn’t silence her. “One day, a year before Lady Bird died in 2007, her daughter Luci called me from Texas. She told me her mother had just finished listening to my book on Abraham Lincoln. Lady Bird wanted me to know how much she loved it. Luci asked me to wait and listen, and, after a pause, I heard the clapping of Lady Bird’s hands-beginning softly, then rising in intensity and volume. I was greatly moved by Lady Bird’s graceful gesture.”

Working on this book gave Kearns and Goodwin an opportunity to revisit history, but it also boosted Goodwin’s spirits as his own health declined. “I want to live long enough to finish the book,” Goodwin said. “So long as we were working together, so long as we were opening boxes — learning, laughing, discussing the contents —we were alive,” Kearns writes.

Kearns is an incredible writer, I expected that going in. What I discovered was how important Richard Goodwin was in voicing what became important social planks in the lives of Americans. The running commentary and reflection of both Goodwin and Kearns provides great perspective and personal history to the events.

For students of recent American political history, this is an important read. I enjoyed it, and came away with an even greater understanding of a decade I continue to learn about.

5/5

Leave a comment