Oliver Stone is a polarizing figure. He’s got some very different ideas and divisive views. He’s unquestionably written and directed some amazing, and sometimes controversial, feature and documentary films.

It’s difficult to separate Stone’s politics from his films; most of the films he’s written and directed incorporate deeply held beliefs. There’s nothing wrong with that, but one should understand the context behind the subject matter.

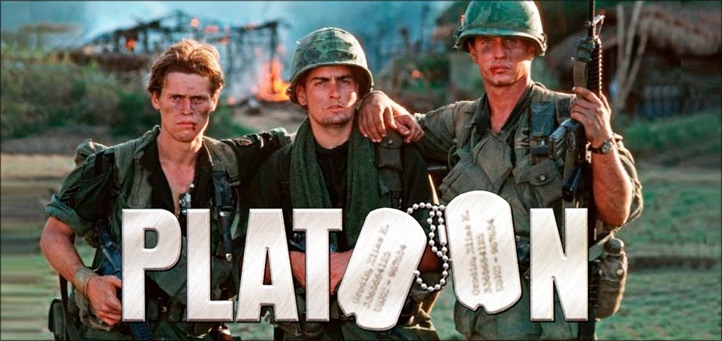

Written five years ago, Stone tells his story and how it influenced several of his defining films. Here’s a guy, without a tether for his youthful rage, volunteers for the draft and asks for a frontline position, is sent into Hell, and somehow survived with a few wounds and more rage. Chasing the Light (2020, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt) is subtitled: How I Fought My Way Into Hollywood From the 1960s to Platoon. That’s a mouthful.

Stone describes a pretty messy childhood, but one that gave him as much confidence as rage. Disinterested in completing studies at Yale, he heads to Southeast Asia, then works his way back aboard a ship. He enlists in the Army and does 15 months in Vietnam, most in infantry combat and long-range reconnaissance roles.

“If I didn’t have the courage to take my own life, perhaps God, in whom I was raised to believe, would take it for me in payment for my ‘sins’ hubris.”

It’s fairly obvious that his parents’ failing marriage and his experience in Vietnam are seared in his early years as he tried to get his footing in Hollywood. I’m not trained in psychoanalysis to probe his psyche (although he engages in it), but the rage and his need to make sense of his world underscores his work. Thankfully, screenwriting embraced those qualities and Hollywood took notice of Stone’s writing. The storytelling talent was there, enhanced by his drive and how deep he dug, turning over rocks, land mines and political untruths in his search for truth.

For me, the best parts, aside from his Vietnam stories, are about the agonies and challenges of his early movies. Stone’s life forever changed after the success of Platoon, but it was a hard road there, and the book really focuses on the successes, but predominately the failures, by him and others, leading up to the reception of Platoon (1986).

Stone’s first significant film job was co-writing and directing the low-budget Seizure, a horror film that was panned and no one saw. It would be four years before his next filmed production, and with it he hit a homerun, adapting the book for Midnight Express (1978), and receiving the Academy Award for Best Adapted Screenplay. That event should have fast-tracked his career, but instead into one of detours and bad choices, both personally and professionally.

Having said that, those years were a very fertile creative period, it was also a time of excess and pain. Stone doesn’t come off as a happy guy, even when his film projects are successful or his family life is solid. There is this dark cloud of turmoil and doubt that hovers over him. Stone’s next project was The Hand (1981), a film he directed from his original screenplay. Another horror film, The Hand tanked, but it was a major studio film with an A list star, Michael Caine, who admitted he took it for the paycheck.

“The Hollywood community, given the nature of the town, seemed to delight in The Hand’s failure. At least, that’s how I felt. After all, I’d come out of nowhere and won an Academy Award for Midnight Express. Did I deserve one? So many people wanted to direct in Hollywood that the cynics were happy to see the comeuppance of someone already successful failing.”

While his directing career stalled, Stone was a sought-after screenwriter. He adapted Conan the Barbarian books for the screen, but was disappointed by what director John Milius and producer Dino de Lautentiis did with his script. Next came the screenplay for Scarface, perhaps his most controversial film. Stone had his own raging cocaine habit, these were the 1980s after all. Scarface was all about the cocaine trade and the violence surrounding it. Stone took some of the plot elements of the 1930s film and built it around a Cuban immigrant who rises through the crime organization to become the drug-crazed leader. Stone’s research took him into the drug trade; he hung out in Miami with law enforcement, and visited places in the Caribbean where he met the real players, getting a little too close at times. Scarface was heavily criticized and failed to turn much of a profit. Stone is proud of the film and still believes that it is very misunderstood. It’s over the top in my opinion, yet is loved by many because of the violence and outrageousness. The failure of Scarface stung Stone. Why had it not connect with audiences, and why did critics see an entirely different meaning to the film? His struggle to gain a larger audience and turn controversy into engagement, would plague his entire career, but there would be shining moments.

Stone had been writing various screenplays that were floating around town, primarily Platoon, his personal Vietnam story. Vietnam films were yet popular, even though a few had been moderately successful; the Reagan Presidency would help create an audience for war-related films again. Stone was approached by Michael Cinino (The Deer Hunter, Heaven’s Gate) about co-writing Year of the Dragon. The Cinino-directed film didn’t turn a profit and garnered mixed reviews including criticism of stereotypical views of Asians. Stone says he was disappointed in the film and Cimino’s direction.

Another adaptation Stone worked on was the book 8 Million Ways to Die, by crime writer Lawrence Block. Originally, Nick Nolte was to star and Walter Hill was to direct, but it fell apart and went into turnaround; then the script was rewritten and recast with lead Jeff Bridges and director Hal Ashby. Stone wasn’t involved in the rewrite, which moved the story from the gritty streets of New York to the smooth pastel boulevards of L.A. Stone hated the result and the film sank into abyss of mediocrity.

Salvador was a story that Stone adapted with photojournalist Richard Boyle on Boyle’s exploits in El Salvador, although heavily dramatized and blended with a heavy dose of Stone’s political/jungle military intrigue. Filming was fraught with problems and director Stone would survive it, and despite some decent reviews, the film was orphaned by the distributor and failed at the box office. Stone was nominated for awards for the script, but the filming and post-production process were crushing with problems, battles and disappointments.

“I also realized two things, both painful: (1) although I’d been deeply involved for a year in Salvador the country, not many people in my own country cared at all about this small nation, this shit hole” we were helping to ruin; and (2) I’d overestimated my film. It was exciting, fresh, made in spite of overwhelming odds, but it was not “great” —and that fell heavily on my own shoulders. But I was proud of it. I’d achieved what Marty Scorsese had asked of us in film school: “make it personal.” I’d made the Salvador story mine. I knew the effort we all made, and I knew”

Included in Stone’ film is a depiction of the rape and murder of four lay missionaries in 1980 by Salvadoran military men.

Platoon was to redirect Stone’s career. In the 1980s, Vietnam was a popular subject: Full Metal Jacket, Hamburger Hill, Rambo 1 and 2, Missing in Action, Uncommon Valor, Good Morning Vietnam among others.

Salvador had been a learning experience for Stone. The challenge was to tell his story, and to keep it entertaining. Salvador had turned many people off, plus it was a country few people knew much about and a civil war that most Americans didn’t care about. “Perhaps the mood on Vietnam was shifting in our favor. I have no idea why, but Mike Medavoy now cautioned me to make Platoon “better than Salvador… non-gratuitously … don’t rub our noses in the violence; make each character an involving human being for the audience.”

Platoon had a bigger budget and greater studio support than Salvador, the script actually had multiple studios interested in distributing it. Filming in the Philippines turned out to be nearly as problematic as Mexico was for Salvador.

“What possible women’s audience could there be for Platoon? Robert Daly would certainly be thinking this now. My sense of violence was too realistic and harsh for most Americans. Maybe I was just too different, “fucked up” by Vietnam. My very nature was unacceptable in the fantasy world of moviegoers.”

Platoon was Stone’s story. He drew heavily from his own experiences in Vietnam, and some were nightmarish.

“I wanted to kill him, and I could’ve gotten away with it,” Stones writes about another soldier. “We were spread out in pockets, two or three men around me, no sergeants with us. The other soldiers were busy searching other parts of the village. But I didn’t kill him; there was the thinnest of lines that prevented me, the thinnest thread of humanity in me that didn’t break.”

Fragging was the term given to killing one of your own. Revenge, justice, whatever you wanted to call it. The term is very controversial as some Army officials refuse to believe it happened, yet it comes up in Stone’s recollections as well as many others who saw it.

Stone knew that his story would involve the yin and yang, the angel and the devil, and it revolved around two sergeants from the film.

“I didn’t really wake up until I was thirty years old—in 1976. I was not the kid I thought I was. I was really the child of two fathers-Barnes and Elias, who represented this dividing war for America. I was darkened. A part of me had gone numb there … died, in Vietnam, murdered. My story would be about the lies and war crimes, which were committed not just by one platoon but, in spirit, by every unit. The specific crime in this case would take place in a village with the lead sergeant, Barnes, murdering a villager in frustration because he feels they are collectively helping the enemy to destroy his men. The other sergeant, Elias, lesser in rank, would turn on him and resist.”

“I was materially happy with myself, my position in the world, my marriage to a beautiful woman, but I was miserable inside,” Stone would write after the years of struggle gave way to success. Yet, he continued to have this internal turmoil. “I was prepared to be alone, to be isolated by my beliefs. But I also began to believe, like many exiled writers, the worst about myself.”

Platoon was a lauded film, a critical and commercial success. However. “I murmur, sad because I know that although I finished the film, a part of it will never be there, any more than the faces of the gawky boys we left behind in the dust. As close as I came to Charlie Sheen, he would never be me and Platoon would never be what I saw in my mind when I wrote it and which was just a fragment, really, of what happened years ago.”

The Directors Guild of America awarded Stone the Outstanding Directorial Achievement in Motion Picture for Platoon. “The DGA gold plate is enormous, and holding it, I felt solid-like the writer-director I’d wanted to be since NYU. I’d arrived. I could honestly, for the first time, call myself successful.” It was the top of the mountain. To be recognized by the DGA is every director’s dream.

The book ends with the release of Platoon and the impact it made on his life.

“I’d been chasing the light a long time now. I’d felt its power. I was now forty years old, proverbially at the halfway point. It’d been a remarkable two-film journey from the bottom back to the top of the Hollywood mountain. With Salvador, I’d slung the stone hard and far, and it had given me a foothold. And with Platoon, I’d managed to crest into the light. Money, fame, glory, and honor, it was all there at the same time and space. I had to move now. I’d been waiting too many years to make films. Time had wings. I wanted to make one after the other in a race against that Time—I suppose really a race against myself in a hall of mirrors of my own making. Thirty years now, I look back and realize I had no idea then of the storm that was coming, but I did know instinctively that I’d reached a moment in time whose glory would last me forever.”

Platoon was nearly 40 years ago. Stone’s career has taken some interesting turns, along with his reputation. That aside, Stone’s moment in time, Salvador and Platoon, will stand as both his biggest learning period and his greatest success. Looking back, like growing old, is not for sissies.

Did I enjoy the book? Not always, but I was invested, once I turned the first page. Like him or hate him, Oliver Stone is one of the most important filmmakers of our time. There’s that word time again.

Leave a comment