Martin Barre was not the original guitarist in Jethro Tull, but he was the heart of the band’s sound. Barre came onboard after the first album, replacing Mick Abrahams in 1969 until Ian Anderson dissolved the band in 2003. Barre was not asked back when Anderson resurrected Tull. While Anderson wrote vast majority of the Tull albums, it was Barre’s guitar that was the trademark sound, in my opinion.

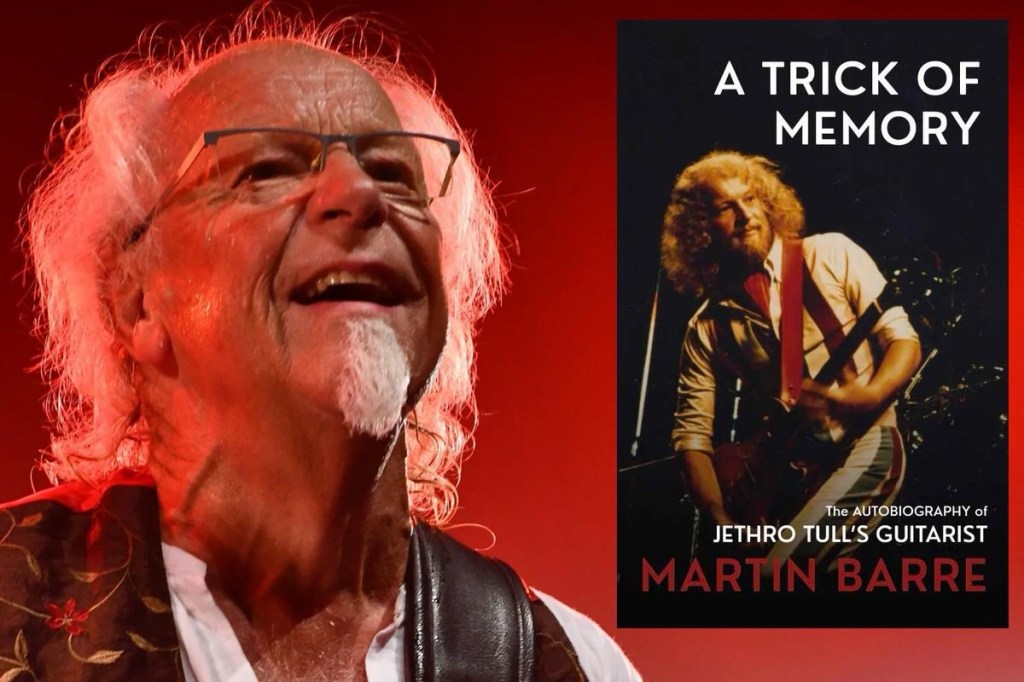

A Trick of the Memory (2025) is Barre’s story. It’s one of the most enjoyable rock memoirs I’ve read. Early on, Barre alerts readers that’s it not a “kiss & tell”, if fact, he doesn’t event mention he has three kids till the end of the book!

Naturally, the story I was most interested in was how he hooked up with Jethro Tull. As Barre tells it, he auditioned in a basement with any, and everybody, who owned a guitar, and walked away certain that he hadn’t done well in his playing. Although Anderson rang him up days later and said he had made the shortlist, they were instead going with Tony Iommi, who would anchor Black Sabbath for more than half a century. Barre summoned his courage and called Anderson, who told him things hadn’t worked out with Iommi; a second audition with Barre was held, with further playing with new music Anderson had written. Barre was asked to perform several concerts on the road with the band, still, no decision on his hiring.

Anderson had changed Tull’s sound after Abrahams left; the blues were out, a more expansive style of rock was in. The blues would always be part of Tull’s musical fabric, but other shades of the musical spectrum would be blended-in. Abrahams was a greatly respected blues guitarist who later had success with Blodwyn Pig. I mention this because Abrahams passed away on December 19, 2025, at age 82.

What is strange is that Barre was also a flute player; two flute players in the same rock band. What are the odds? I learned a couple of other fan facts about Barre. He runs marathons and has been a runner since his youth. Barre is also a water skier. I’ve never heard of a Brit who water skied.

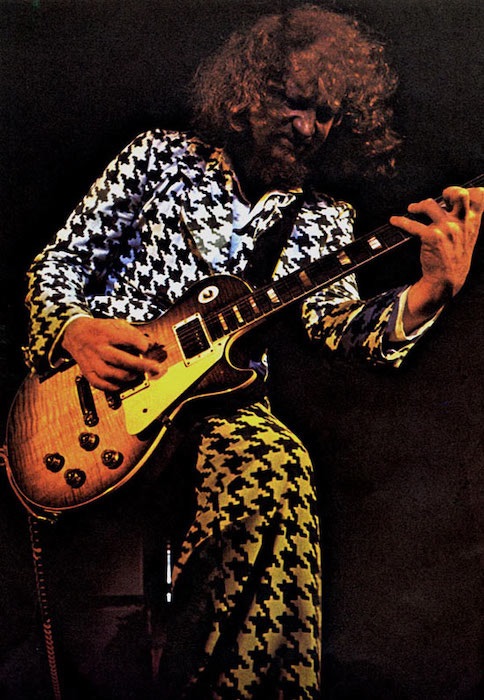

Barre writes of his early days with excitement, gratitude and wide-eyed optimism of a new world at his feet. A product of humble beginnings, his story is like so many other musicians who grew up in post-war Britain, nearly starving and living in cold and bug-infested accommodations. Thankfully, when he joined Tull, his life improved quickly. The Tull audience was building quickly. The band was immediately off to America for three months; he was living the dream, America. Barre speaks very respectfully of all the other musicians he’s encountered along the way, with very minor exception. He was in awe of Jimi Hendrix, whose band toured with Tull in those early days. Barre is quick to point out that he studied and learned from these other bands.

If I have a complaint, the book is awfully brief. I had many questions when I turned the last page. Of course, everyone what the skinny on why Anderson shut down the band and then didn’t ask Barre to rejoin. It obviously was a surprise to Barre, and he seems to hold no grudge, but it had to hurt after 43 years. There’s very little in the book about Ian Anderson, and what is written, is nice. Barre is a good guy. Anderson often changed out members of the band, quite unceremoniously. The most burning question is why Barre didn’t get more songwriting credits on Tull albums. He wrote the guitar parts and helped flesh-out Anderson’s ideas. What Barre didn’t have to say is whether Anderson is controlling – he doesn’t have to.

I’m a big Jethro Tull fan, and much of it is because of the guitar player. Thanks Mr. Barre! If you can find this book, read it.

Leave a comment