Leni Riefenstahl is a divisive subject. That should come as no surprise.

Riefenstahl (2025) is a documentary on the life and career of German filmmaker Leni Riefenstahl. I found the film disturbing and difficult to watch. I’ve seen several of her films and I’ve studied World War II, so very little is left to surprise me. Riefenstahl was a creative and passionate filmmaker, and she was the perfect artistic weapon for the Third Reich. Her films are amazing. And frightening.

Helene Bertha Amalie “Leni” Riefenstahl began as an actress in mountain films, a popular type of film which showed the the spirit of adventure, challenge, and the delicate balance with nature. These films exemplified health and vitality, and portrayed mountain climbing as an allegory for triumph and overcoming setbacks. These films showed Germanic spirit in a glorious, uplifting manner. The climbing work was very dangerous, and Riefenstahl was the only woman in the set. Riefenstahl was driven; she was a woman in a man’s world, pushing herself to create opportunities and seize them. Confidence was not a problem. She survived being taught to swim by being thrown in the lake by her father; he had expected a boy, not a girl. Riefenstahl started directing her own films including The Blue Light (1932) which caught Adolph Hitler’s attention.

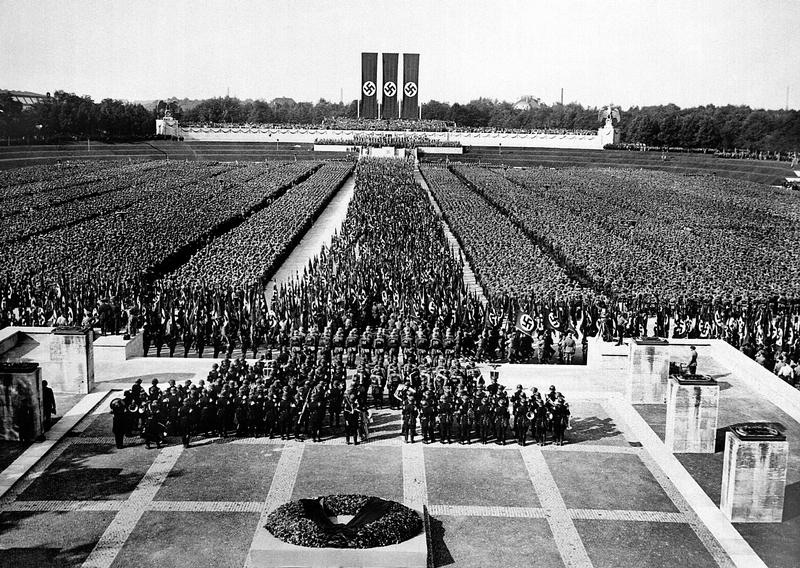

Riefenstahl who made numerous films for Hitler and the Nazis. Triumph of the Will (1935) is her most notable for showcasing the Nuremberg Congress in all of its fanaticism and grandeur – it’s capturing the spread of the Nazi doctrine to the German masses. The film captures several days of rallies, parades, impassioned speeches, highlighted by dramatic sets, lighting, music and imagery in is one of the most horrifying events ever depicted on film.

Riefenstahl dismisses any and all criticism of her role in the spread of Nazi principles through her films. Olympia was her Nazi funded documentary of the 1936 Olympics. She was provided a huge budget to show the world National Socialism and racial superiority. Again, in a 1970s German talk show, she vigorously defends herself in directing the film, saying that she did not alter or enhance the event. “Why do people always accuse me of embellishing things in that film?”

She worked very hard on influencing public opinion of her when she published her memoirs. She works ten years on her book.

Public opinion of her in her later years was widely split. In this film, recordings of her phone calls and excerpts from letters showed that her support was strong, across a wide range of German people. After appearing on the talk show that I referenced above, where a woman of similar age spoke against Riefenstahl’s defense of making films for Hitler, Riefenstahl received fan mail and even support from some journalists. Where did this support stem from? Riefenstahl was quite good stirring the consciousness of older Germans who felt angry at being blamed for Hitler.

During another filmed interview, the interviewer asks Riefenstahl about her visits from Josef Goebbels and Riefenstahl vehemently denies it, despite entries in Goebbel’s own diary, she strongly rejects the question and the efforts in introducing something she denies and angrily ends the interview.

In her notes and conversations with Hitler Riefenstahl gushes, the film shows her hero worship of him. Describing when she first heard Hitler speak, he started by saying: “My National colleagues.” She indicated that she “was trembling and had hot sweats…captured, as if by a magnetic force.”

Riefenstahl is asked by Hitler to film the invasion of Poland. After several weeks of filming in Poland, she abruptly leaves, and requests to be relieved of her position as war correspondent. She meets a Nazi major and married him. While filing in Poland, she was accused of complicity in the murder of 22 Jews who had been working in a ditch. When she allegedly said “get rid of the Jews”, meaning get them out of the camera frame, it was communicated to the officer present as “get rid of the Jews!”, and they were shot. In 1952, a letter surfaced that outlined this accusation, which she denied. The fact was, a massacre in Konske had taken place, and photos in Riefenstahl’s archives were found that supported the accusation.

After returning from Poland, Riefenstahl began work on Lowlands, a film financed by the Nazi party, was mainly filmed from 1940 to 1944, but not finished and released until 1952. In the film, Riefenstahl used extras with a specific “Roma look”, children and adults of Roma and Sinti background who were held in Nazi collection camps. Riefenstahl claims that she met with all of the extras after the war, that they all survived. The names of those who went to Auschwitz are recorded, and the records shown in this documentary. The Nazis were great at record keeping.

Elsewhere in the documentary, Riefenstahl uses the “we didn’t know” excuse for not knowing about or understanding the purpose of the camps. “Only for spies” misses the notion of knowing anyone who simply disappeared because of being Jewish or intellectual or being against Hitler. Jews that she know all went to America.

Riefenstahl paints herself and other German citizen as victims, who saw their world collapse by the war, who experienced, and still suffer from, great trauma from those events. That position got her sympathy and agreement from other Germans who felt accused for the crimes of others.

In 1993, Riefenstahl during an interview, she was shown a TV report of violent protests against immigrants. Riefenstahl refused to accept that things like this happened before, she was quick to cut off the interviewer and saying she would not comment, but she angrily does. “It’s all lies! If you speak the truth you are labeled a neo-Nazi!”

At the end of her life, Riefenstahl was still trying to control her narrative. In the eyes of some, she will remain the brilliant artist who was unfairly tainted by the subject of her art. It was this brilliance that was so frightening. The art and the artist were one. She shrewdly knew how to manipulate audiences with her films, and she continued to manipulate (or try) to control what others thought of her. Riefenstahl spent a lot of her time after the war in court, there were several denazification trials where it was not proven that she was a member of the Nazi party but was labeled a Nazi sympathizer. She filed many lawsuits against those she said libeled her.

It’s difficult to separate the artist from the art in reviewing this documentary. Her association with Hitler and the Nazis is very much her life, and she used her artistic skills to showcase Nazi ideology, and link it to Germanic life. Her films delivered the hearts and minds of Germans (and other sympathizers) to the Reich. Her later denials are ridiculous, as were her efforts at sympathy.

I haven’t mentioned the film’s writer and director, Andres Veiel, and producer, Sandra Maischberge. Together, they have made an outstanding film, one that is uncomfortable and riveting. Riefenstahl left behind 700 boxes in her archives, mostly never before seen material from her life. In a sense, Riefenstahl provided her own story, but not the one she wanted to tell.

Leave a reply to greenpete58 Cancel reply