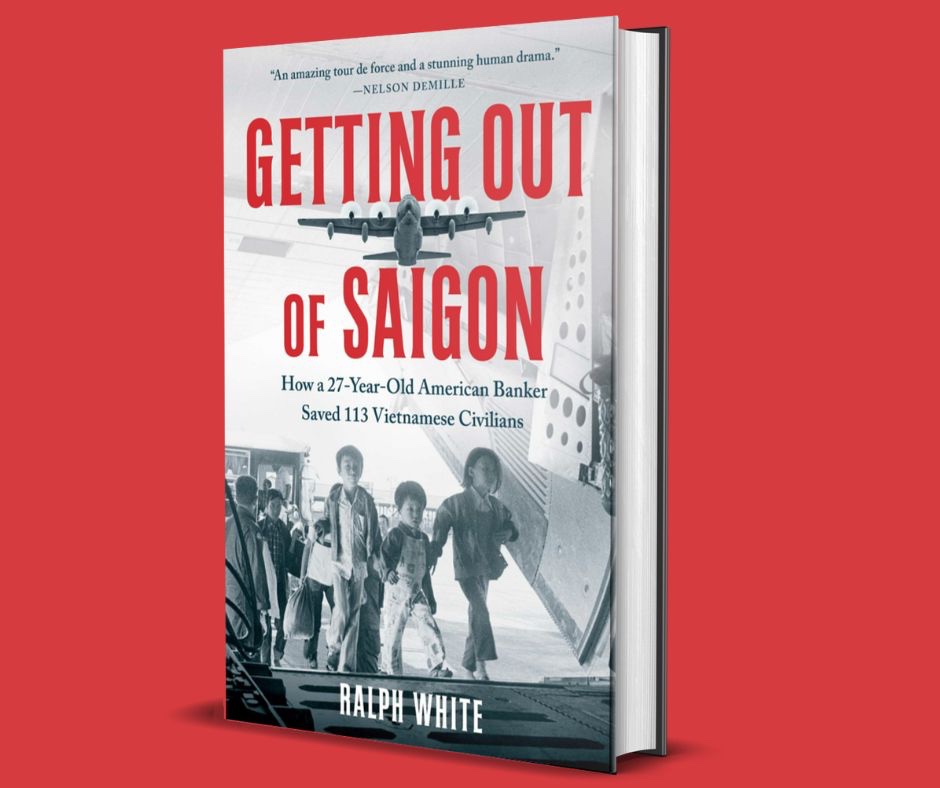

It’s been nearly 50 years since the last helicopters of Americans, and Vietnamese evacuees, left Vietnam and closed that chapter. Well, not exactly. Stories of that time and place continued to be told, and here is quite a riveting tale of compassion and heroism.

Beginning of the end timeline:

January 1968: The Tet Offensive.

March 1968: President Johnson halts bombing in Vietnam north of the 20th parallel.

November 1968: Richard M. Nixon elected president.

1969-1972: The Nixon administration gradually reduces the number of U.S. forces in South Vietnam.

February 1970: Henry Kissinger begins secret peace negotiations with Hanoi.

May 4, 1970: National Guardsmen fire on anti-war demonstrators at Ohio’s Kent State University, killing four students and wounding nine.

June 1971: The New York Times publishes a series of articles detailing leaked Defense Department documents about the war, known as the Pentagon Papers.

January 27, 1973: The Selective Service announces the end to the draft.

January 27, 1973: President Nixon signs the Paris Peace Accords, ending direct U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War.

January 1975: President Gerald Ford rules out any further U.S. military involvement in Vietnam.

The story begins…

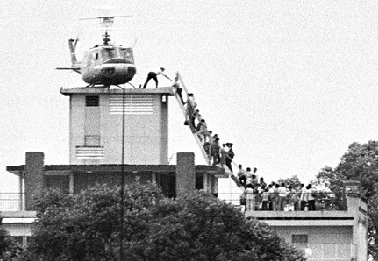

April, 1975: South Vietnam was falling to the communist North, the Paris Peace Accord was a sham, and Americans and other Westerners were fleeing, or had already fled. Officially, the U.S. ambassador was convinced the North would be repelled, even though Congress had just denied hundreds of millions in more funding, and President Gerald Ford would proclaim the war for America was over. Even though top embassy officials in Saigon refused to seriously discuss evacuation plans, other embassy staff were quietly, and contradictory to orders, organizing planes and boats to get at-risk Vietnamese out of the country. We all remember the helicopters on top of the U.S. embassy making countless trips to fly Vietnamese to American ships. The fall of Saigon would be a clusterfuck. For those of you not old enough to remember the war in Vietnam, think Afghanistan. Very similar.

The relationship between South Vietnam and the U.S. was complicated. The U.S. was not an occupying force, at least officially, though the people may have felt the same way as they did about the French. The South Vietnamese government was not an active party to the Paris Peace Accords, so I imagine the U.S. withdrawal was felt like abandonment. This feeling trickle down to the average South Vietnamese.

White wrote this about a young girl he wanted to help. It really sums up the American experience in Vietnam. “We thought we were bringing them liberalism and they thought we’d come to fuck them. Maybe the whole war was just a decade-long misunderstanding.”

White writes about the importance of the battle of Xuam Loc, what appeared to be the last major battle of the war. Although the South Vietnamese held for ten day before retreating, those ten days were critical to those seeking to leave Saigon.

Although other foreign companies had already closed shop, Chase Manhattan Bank intended to stay until soldiers from the North were standing in the customer line. Chase executives had been burned already, during the Korean War, bank officials in Hong Kong, fearing an invasion, fled. The war never came to Hong Kong and Chase executives never lived it down. Now, the plan was to keep the Saigon operation open as long as possible. Their current Saigon Chase bank manager was moving to Hong Kong (how ironic) and a young executive, Ralph White, who had experience working in South Vietnam, was selected to lead the Saigon Chase office.

White was picked because of his past experience working in Southeast Asia and some ability with the language. His unflappable nature and savvy would be valuable resources in this story.

“I would pay women who were in the sex industry to teach me the language,” White told the Christian Science Monitor. “I did it in Thailand, I did it in Vietnam, and I’ve done it in other places. (I’ve never paid for sex.) It’s a relatively inexpensive language lesson.”

White would keep the operation going, while it was safe, but he knew from the start that his most important job was to get his South Vietnamese employees and their dependents safely out of the country. The clock was ticking as thousands of North Vietnamese soldiers and an untold number of Vietnam Cong were already in the South. The story begins with White’s arrival in Saigon, meeting U.S. embassy officials, his new staff and sizing up the situation in Saigon. He had worked in the city four years earlier; a lifetime ago. The impending doom could be measured were by the currency exchange rate; the South Vietnamese dong was rapidly losing value. Another indicator was the amount of newspaper censorship by the government; the more white space meant more bad news. And finally, the length of the line outside the bank waiting to withdraw funds.

White’s story sounds like it was written by Frederick Forsyth or Joseph Conrad as a hyped-up thriller, but it’s not fiction. The story takes place over three weeks in April, 1975, and is divided into separate days. It’s amazing how much White accomplished each day and what he learned about the war, and who was friend or foe. In other words, it was difficult to tell the good guys from the bad guys, they weren’t always who you thought they were.

The bad guys weren’t just the North Vietnamese army (PVAN) and Vietcong, the South Vietnamese government and army (ARVN) put up multiple physical and bureaucratic roadblocks to evacuating South Vietnamese who worked for Americans and other foreign interests. Exit visas, which were difficult to obtain, were suddenly required for Vietnamese citizens wanting to be leave. The South Vietnamese army set up checkpoints, searching for and executing suspected deserters and draft avoiders. According to White, Ambassador Graham Martin refused to help get Chase employees and their dependents out of the country, despite an agreement with Chase officials.

“It was heartbreaking that the likes of Ambassador Martin and Deputy Chief of Mission Lehmann were so brazenly ambivalent about the fate of the Cuongs and their countrymen. The absolute best Cuong could expect if Chase failed to get him out was four or five years in a reeducation camp, after which his kids might not even remember him.”

Ralph White

At the ARVN checkpoint, outside of the U.S. airbase, a South Vietnamese Captain boarded the bus that carried White and part of his employee group and dependents. White was carrying a revolver and intended to use it, if the Captain tried to remove one of his people.

“But I couldn’t kill this guy for merely boarding my bus. Until he barked an order in Vietnamese to take one of my boys off, I had to allow him to live. But point at one of my boys and demand he stand up and the captain’s life would end. Neck and shoulders relaxed. Regular breathing. Eyes on his heart and lungs. As the sole American on the bus, other than the driver, I must have been fairly conspicuous. It was too late for me to stop. Id already made the decision to kill him. Right here, Captain. Come back here and check somebody’s ID. We could settle this whole foreign policy misunderstanding right now, or the little piece of it that concerns the two of us.”

The Captain looked around scaring everyone onboard. His eyes and White’s met. He made no effort to remove any male passengers, and waved the bus onward.

Fortunately, embassy underlings were quietly running humanitarian efforts to evacuate vulnerable Vietnamese. These were some of the good guys, who included the American military handling the evacuation, and various contacts White established in Saigon. White tells an incredible tale of help received from the brother of a young Vietnamese prostitute, the brother being a North Vietnamese agent.

In great detail, White paints a thrilling and dangerous portrait of a city, and country, about to be taken over and many perhaps executed, either because of their political or military positions, or from their association with Westerners. With each chapter, the tension mounts as the PVAN nears and the desperation of those fleeing their approach becomes more pronounced. White is a great storyteller, not just of the facts, but this mission is personal to him as his manifest of lives to be saved, continues to grow. Counting himself, White was responsible for evacuating 113 from Saigon, mainly bank employees and their families.

I reached out to White and asked if he ever felt over his head by the danger all around him. “I didn’t feel in danger myself. I could get out anytime. But staying to get my employees out did involve a higher order of risk. The chance that luck played only became obvious to me retrospectively.”

White explains at the end of the book how he was able to construct and verify the details of a complicated story almost five decades ago.

White is particularly thankful for the help of Shep Lowman, the political officer in the U.S. Embassy [in Saigon], and Ken Moorefield, who was operating as the ambassador’s aid at the Evacuation Control Center, the two of them were absolutely vital to my success. Along with Col. [William] Madison at the Defense Attaché Office,

Leave a comment