Samuel Fuller was a legendary filmmaker in Hollywood. As the maker of mostly B films, he did more with less, and fought to get his told hard-edged stories to the screens. Even when he had deals with the major studios, his budgets were modest. On more than one occasion, Fuller would turn down a studio project, to protect his creativity and autonomy.

For those unfamiliar with Fuller’s work, he began as a contract script writer of films in the 1930s and 1940s. As a teenager, he had worked for the New York Evening Graphic as a reporter. Fertile ground as a writer of Westerns, war and crime films. Fuller also published a novel, The Dark Page.

Serving in World War II, Fuller saw action all over Europe and North Africa as an infantry man. Instead of reporting about the war, he requested to be an infantryman, where he could live it. These experiences served Fuller in his writing, witnessing the inhumanity and suffering, the senseless and the corrupt, and the goodness that survives the darkness. Fuller’s films could be classified as noir, but that’s too simple a definition for the wounded psyche that spins at the heart of his best films.

Fuller, like Budd Boetticher, worked around the fringe of the Hollywood studio system. Later, filmmakers like Altman, Hellman, Cassavettes, Romero, Warhol and Corman found challenge and success working independently or affiliated with independent production companies that could secure money and distribution for small-budget films.

The best way to learn about Fuller’s films is to see a few of them. For this blog I picked out a few films to watch and discuss. The term “hard-boiled” comes to mind when I think of Samuel Fuller. His films often hit you like a ton of bricks, subtlety is not an adjective one normally uses in discussing Fuller, although his film, The Big Red One, his most personal film, is very subtle for a war film. Fuller preferred to address the issues in his films realistically and directly. To do so often meant working independently and/or with smaller budgets. One has to respect Fuller for his convictions and taking risks. He was not afraid to confront racism, poverty, mental illness, crime and other societal issues in his films. Even though he worked with smaller budgets, his films were professionally done and praised for their production and unflinching realism.

[Note: Fuller’s memoir, A Third Face: My Tale of Writing, Fighting, and Filmmaking (Alfred A. Knopf, 2002), is a great read about his life and films. This blog is not a review of that book.]

I Shot Jesse James (1949)

Fuller’s feature directorial debut. This is not the story of Jesse James, rather the reckoning of assassin Bob Ford. Fuller was a screenwriter at that point who wanted to direct; he got his chance by working cheaply as both writer/director.

Fuller took a magazine article and turned it into a fictionalized story that’s a pretty good one. The cast includes John Ireland as Ford, Barbara Britton as the love interest, Preston Foster as Kelley the rival. Reed Hadley, who looks a lot like John Carradine, is Jesse James. Tom Tyler is the vindictive Frank James.

I don’t know how much of this is fiction besides the romance and rival, but the scrip is a story with twists and turns. Fuller keeps the pace moving and his character have depth and obviously benefit from a fine cast. According to Fuller, this was a love story, but it was Ford who loved Jesse. That didn’t make producer Robert Lippert very happy, although the tidy box office profit did. “The real aggression and violence in the film would be happening inside the head of a psychotic, delusional killer,” Fuller said in his autobiography. “I wanted to show Ford realizing that he’s sick, then show him as he sinks deeper into his sickness.”

The Baron of Arizona (1950)

What a whacky “Western” this is, even though it is very loosely based on a real situation. Vincent Price plays a swindler out to gain possession of all Arizona territory by way of forged documents. Fuller wrote the screenplay and directed. While it is usually mentioned as one of Fuller’s best films, I find this costumed melodrama to be silly and Price to be overacting.

Fuller was praised as improving his direction over his first film, I Shot Jesse James. I disagree. While his staging and technical elements may have evolved a notch, his storytelling decreased by much more than that. The independent producer Robert L. Lippert believed this soggy fluff would be a hit, with voiceover narration by Price’s character to guide the emotional tract of the film. Too much of the action takes place in the monastery and the story moves at a snail’s pace. Fuller does not have command of the material. Price is more effective as a scoundrel rather than a romantic lead here.

James Wong Howe, arguably the greatest cinematographer of his time, asked Fuller to shoot the film, taking a fraction of his usual fee. Fuller said Howe have the a gothic look, unusual for a Western, but it looks beautiful on the screen.

The Steel Helmet (1951)

Gene Evans is Sgt. Zack, the lone survivor as a massacre of U.S. Army soldiers fighting in Korea. He is rescued by a Korean orphan boy who wants to befriend Zack. Zack meets up with a medic and another group of soldiers, a bedraggled lot.

This is a story of warfare and survival much different from the heroic WWII films of a few years earlier. Booby-trapped body of a dead G.I., prisoners hogtied and executed, snipers dressed as peasants, referring to Koreans as “gooks”, examples of a different war.

Evans a great casting as Zack; grizzled, crude and unsympathetic. Evans was not the actor others wanted for the role. Sources said that John Wayne was offered for the role but Fuller turned it down and fought for Evans. Zack shoots an unarmed prisoner out of anger, one of the reasons the Defense Department was unhappy with this film and accused Fuller of making a communist indoctrination film.

This a tough, unflinching war film, full of violence and the prejudice that accompanies war. A captured North Korean major attempts to exploit race with an African-American medic and a Japanese-American, using prejudice in America for his effort to escape. Fuller said when the film was released he was called a communist and investigated by the FBI, and criticized by The Daily Worker for showing American soldiers as “beasts.” Criticism from both sides, but the film went on to do solid business. Evans would appear in several Fuller films and go on to a long and successful career as a character actor.

Later Films…

The Crimson Kimono (1959)

The Crimson Kimono is a love triangle between two police detectives and a witness. Written, produced and directed by Fuller, this the story of friendship and racism, because one of the detective is a Japanese-American. Murder is only one of their issues. Stars Glenn Corbett, James Shigeta and Victoria Shaw.

In 1959, race as a central plot issue was quite a risk. Is it a murder noir or a less on racial prejudices? It’s both. Mixing race and murder was a difficult balancing act; too much or little could stilt or weaken the film. Watching the two men fall for the same woman is quite engaging.

“Though it looked like a pretty conventional cops-and-criminals movie, The Crimson Kimono was almost operatic in its tone,” Fuller said in his memoirs. “I was trying to make an unconventionally triangular love story, laced with reverse racism, a kind of narrow-mindedness that’s just as deplorable as outright bigotry. I wanted to show that whites aren’t the only ones susceptible to racist thoughts. Joe is a racist because he transfers his fears to his friend.”

This is Los Angeles, with large ethnic populations, yet there is something uneasy in how they live, side by side. Mixing, dial up the drama.

As usual, the black & white photography is crisp, and not overly noirish. Fuller has a good eye for tones and textures, how the light magnifies or swallows whole.

You aren’t supposed to enjoy Fuller films, subject matter and tone are hard-edged and you feel that Fuller is showing you what you need, not what you want. There are exceptions. I like The Crimson Kimono and later, The Big Red One.

Underworld USA (1961)

Fuller learned fast. In short time he was writing, producing and directing. Underworld USA is a marvelous noir film. Fuller can not only tell a story, quickly and to the point, he hires talented and cheap actors/crew, and photographs only what’s necessary, in an interesting way. Filmmaking is like an editing the news, less is more.

Underworld USA is tough and brutal. Drugs, whores and murdering children. It’s beautiful to look at, rich black & white photography, courtesy of Academy Award winner Hal Mohr. Fuller uses Mohr’s lighting and camera placements in telling a riveting story featuring a young and brazen Cliff Robertson.

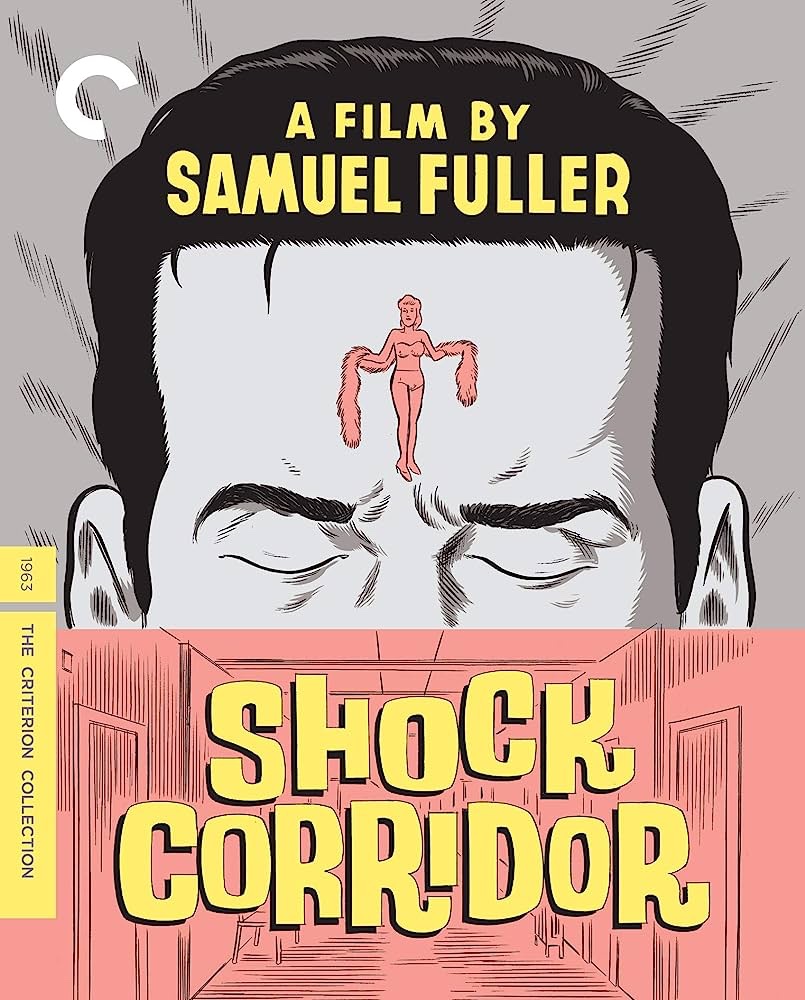

Shock Corridor (1963)

An original script by Fuller, he also directed and produced. A reporter (Peter Breck) Barrett covets winning a Pulitzer Prize so much he is willing to get himself committed to a mental hospital to solve a murder that happened there. He’s successful in getting admitted. That’s when the fun begins.

Fuller has gathered a talented cast. In addition to Breck, Constance Towers, Gene Evans, James Best, Hari Rhodes, Chuck Roberson, Philip Ahn and Bill Zuckert. All familiar faces.

Barrett immediately feels the pull of mental illness as he begins to find and confront each of three witnesses to the murder. Barrett has been coached in acting mentally ill, maybe too well. His girlfriend, who participates in the charade, by posing as his sister, is genuinely afraid for him. He’s been committed to the hospital because of sexual advances to her.

As he works his way through the witnesses he gets sicker and sicker. He’s put in restraints, then later undergoes electric shock treatments. It’s a scary ride; can a sane person go insane by being subjected to the environment?

Fuller uses the story to explore various issues of insanity, sexual obsession, racism, the accountability of developing a device of mass destruction and prejudice toward mental illness. Each of the witnesses bares the trauma of their experiences, driven insane by the savagery inflicted upon them. A sad, but effective commentary about our own self-destruction. Barrett too is broken, his perpetrated by his own obsession to win an award and be recognized.

“My title became Shock Corridor. It had the subtlety of a sledgehammer,” Fuller said. “I was dealing with insanity, racism, patriotism, nuclear warfare, and sexual perversion,” Fuller said of Shock Corridor. “How could I have been light with those topics? I purposefully wanted to provoke the audience. The situations I’d portray were shocking and scary. This was going to be a crazy film, ranging from the absurd to the unbearable and tragic. My madhouse was a metaphor for America. Like an X ray that fathoms a patient’s tumors, Shock Corridor would probe our nation’s sickness. Without an honest diagnosis of the problems, how could we ever hope to heal them?”

And finally…

The Big Red One (1980)

After being absent for nearly the entire decade of the 1970s, Fuller returns with maybe his finest film. He drew upon his war experiences to create a film about a group of green soldiers who fall under the command of a veteran sergeant who teaches them about war and life, as they fight in various European, Mediterranean and North Africa locations like Fuller did.

Working with very little money, Fuller used his tricks of filling the screen with the illusion of a big war movie, using deception and a carefully designed production to feel more grand than it was. In a sense, The Big Red One was an existential war film, full of ideas and visuals that gave viewers a lot to process.

Lee Marvin, very haggard and weary, played the sergeant, a World War I veteran who was a step slower, but a bit smarter, in his second war. The cast is small, but includes Robert Carradine, Mark Hamell and Bobby Di Cicco.

Fuller was interviewed by film critic Roger Ebert and said: “The movie deals with death in a way that might be unfamiliar to people who know nothing of war except what they learned in war movies. I believe that fear doesn’t delay death, and so it is fruitless. A guy is hit. So, he’s hit. That’s that. I don’t cry because that guy over there got hit. I cry because I’m gonna get hit next.”

Fuller’s film is personal, seen through the eyes of the four young soldiers and their gruff, but silent sergeant. Fuller doesn’t need a production the size of The Longest Day or Saving Private Ryan because war is personal, each soldier is fighting his own battle, trying to keep from being killed while inching up the hill or moving across open ground. These four young men watch as other young soldiers die.

Marvin says very little, he doesn’t need to. He leads and instructs by example. His quiet leadership is different than other sergeants in war films. This isn’t a “rah, rah, let’s take the hill, boys,” kind of film. There’s no fake heroism or bloated patriotism here. That may disappoint some; no need for John Wayne leading the charge. Fuller and Marvin actually served in WWII, they saw it up close and personal. Instead of explosions filling the screen, human drama does. In 1959, Warner Bros. offered to finance the film with Wayne as the Sergeant, but Fuller declined. It would take 20 years to realize his vision. Thankfully, he did.

Fuller worked, or wanted to work, right up to his death. He had trouble finding directing jobs, although he was always writing and talking to potential producers about ideas.

Leave a comment