“Dragon Lady” is not exactly a term of endearment for a woman of Asian descent. The term obviously denotes intense power, but also to be menacing, resourceful and feared. It’s never clear if Madame Nhu appreciated the term, but she lived those adjectives. She earned the ire of both men and women, but she was not be quieted or dismissed. While she might have looked like a delicate flower, she was anything but that.

I had heard of Madame Nhu before reading Monique Brinson Demery’s book, but I could not provide any depth on her role in the government. I did not set out to find this book, it found me.

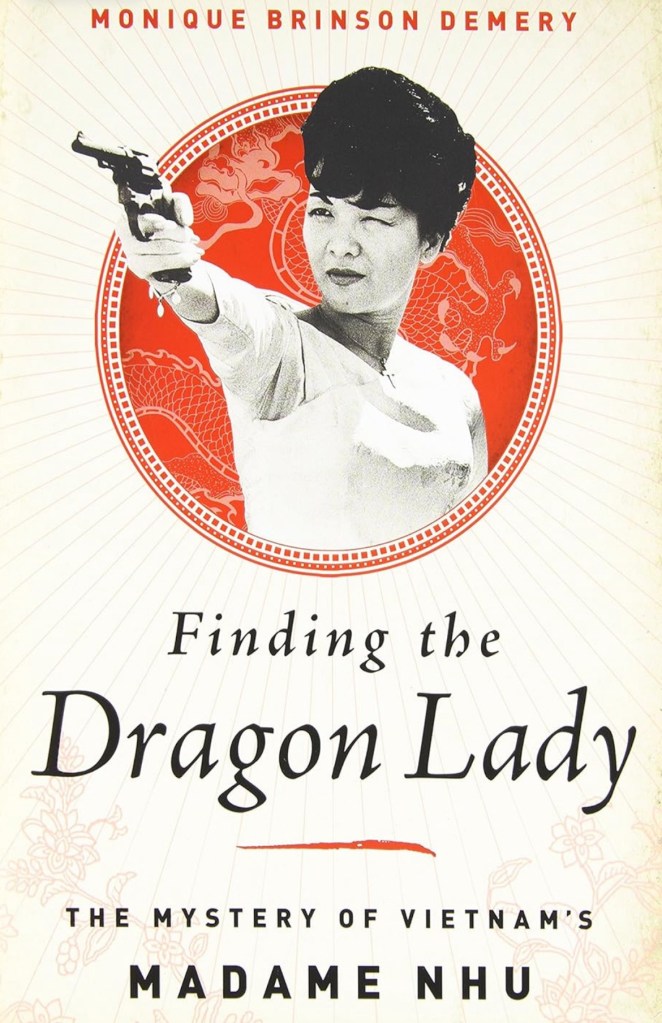

Demery writes a very engaging biography of Madame Nhu, but you get much more. Finding The Dragon Lady, The Mystery of Vietnam’s Madame Nhu (PublicAffairs, 2013) is also a summary of the modern history of Vietnam: from the French to the Japanese, to the French again, life under a forced partitioned agreement, and then a very ugly war for reunification. This is a very readable and personal story of Vietnam, a country battling outsiders, and itself, for identity.

Demery’s research heavily draws upon other journalists who covered Vietnam during the war, like David Halverstam‘s The Best and the Brightest (1972) and Stanley Karnow‘s Pulitzer winning Vietnam: A History (1983). These are not her only sources, but these are outstanding ones.

The Vietnam of today is a trade partner of the U.S., with a powerful economy and peaceful existence, light-years away from the ware of the two Vietnamese nations of an earlier time.

Who was Madame Nhu and why is she worthy of such a place in Vietnamese history? When she was born, Vietnam was a colony of French rule, a poor existence for most Vietnamese, and with very a traditional culture where women had an ordered and defined role in Vietnamese society. Madame Nhu (her married name) would become the sister-in-law of South Vietnamese President Ngo Dinh Diem. Raised in a very male-centric Asian culture, she married at a young age and did her marital duty to produce a son, after two daughters. She married into an influential family of ambitious and politically active brothers. Her husband worked secretly against the French rulers, drawing his wife into a dangerous lifestyle until the French were defeated and left Vietnam. Under an international agreement, Vietnam was then partitioned into two countries, the communist north, and the “democratic” south, with an election to take place in two years to chose a lead for the entire country. That election never happened. Almost immediately, the two countries were at war.

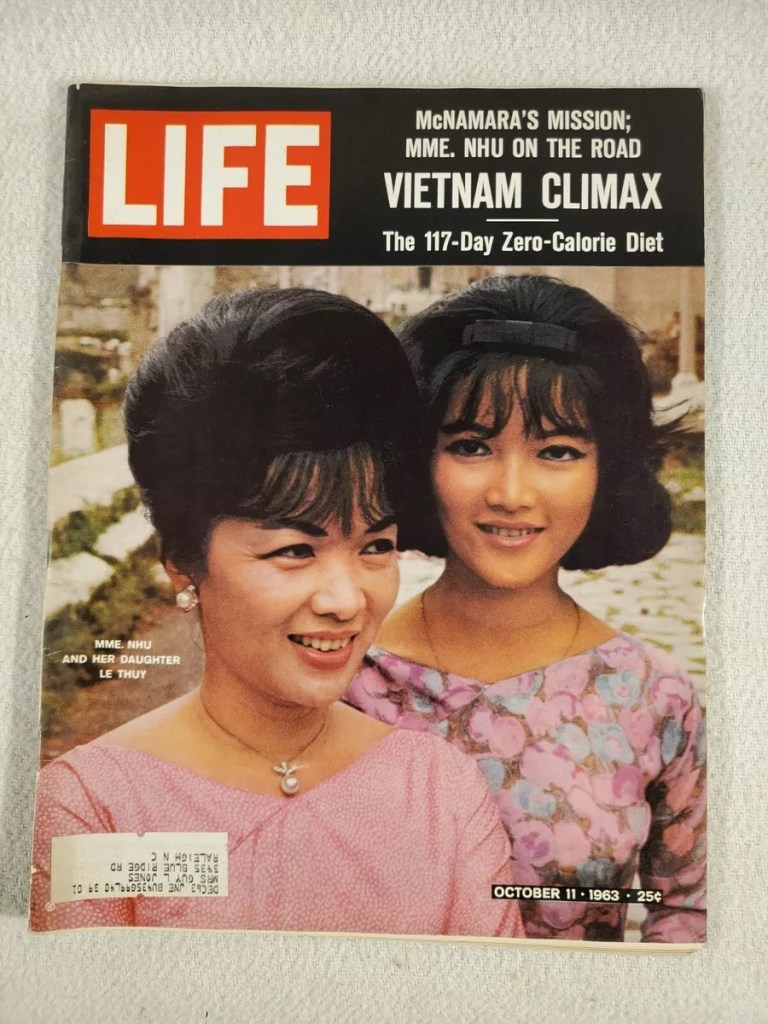

Madame Nhu learned from an early age to fight for what she wanted, tactfully, but ferociously. Her marriage had privilege, advantages and access to power, but was frequently described by her at loveless. Madame Nhu’s brother-in-law, Ngo Dinh Diem, became the prime minister in 1954, and then president in 1955, after ousting the Bao Dai, the former emperor. With the help of Madame Nhu’s husband, Ngo Dinh Nhu, Diem ran South Vietnam with a tight fist, moving family members into important governmental positions. Because the president was a bachelor and Madame Nhu already lived in the presidential palace, he selected her to be the hostess and assist in handling social functions and affairs of state. In essence, Madame Nhu became the First Lady of Vietnam. According to author Demery, Madame Nhu in her new role arranged state dinners, performed public ceremonial duties on behalf of the president, and even traveled on diplomatic missions. Behind the scenes, she was much more than a hostess, she wielded great influence on governmental matters. South Vietnam had a high visibility on the world stage, in no small part due to the First Lady. Distinguished by the beehive hairdo, makeup and elegant fashions, Madame Nhu seemed born for the role.

As if this new role was not enough, Madame Nhu was also a deputy in the National Assembly, the legislative body of Vietnam. Madame Nhu may have been seen as a feminist, but it is clear in Demery’s book that she also saw change as helpful, particularly in developing her own constituency. Madame Nhu introduced legislation that repealed some of the repressive cultural restrictions on women (except it forbade divorce), and with the president’s help pushed it into becoming law. Demery points out that in the north, women were already vital players in Communist activities, working along side men in preparing the country for future reunification.

Vietnam, after the French departed in 1954, was unlikely to ever be a democratic state. The same forces that fought the French were coalescing into what would become the communist state, and the network of communist loyalists in the south, that would effectively battle for control of the rural areas. Diem became the leader in the south, and quickly moved to secure his power through repressive and authoritative means; democratic actions would have to wait until the communists were subdued. Remnants of French colonial rule ran deep, and the average South Vietnamese citizen didn’t get in on the spoils. The French left no effective bureaucratic apparatus, the national treasury was empty, criminal gangs thrived in the cities, and the ruling family preferred Catholics (Diem and his family were Catholic) over Buddhists and other religions. The Diem government was criticized for many reasons including election fraud, their terrorizing secret police, censorship of the media, and being hopelessly out of touch with the public.

The history of Vietnam and the story of Madame Nhu’s life are intricately intertwined. Whether Madame Nhu was actually running the government instead of the Nhu brothers is open for debate, but her position in the family and her aggressive nature made her a strong influence.

An example of her influence came in 1957, when Madame Nhu pushed for adoption of her Family Code legislation. It outlawed polygamy and concubinage, and establishing the right for women to have their own money. Until then, women were unable to have their own money and property without a husband.

Diem’s government was dependent on the loyalty of his military generals. In 1960, there was an attempt coup by a faction of the South Vietnamese military. Unlike other past threats, President Diem was ready to negotiate with this faction to quell the coup. Madame Nhu got in Diem’s face and commanded him to stand firm, send his loyal forces to retake the radio station, and buy time till reinforcements arrived from outside the city. This course of action saved Diem’s government, but according to Demery, Diem and his brother learned something important that day about Madame, something they wouldn’t forget. Madame Nhu would not forget, either.

Also in 1960, the organized effort by the north to overthrow the South Vietnamese government was launched with the establishment of the National Liberation Front, who would work clandestinely in the south, where many communists and friendlies had remained after the defeat of the French, and others who moved from north to south after the partition. Communist forces were already in the country establishing bases in the villages and hamlets, and killing South Vietnamese military and government officials. The reunification effort was already underway.

“Centuries of Vietnamese monarchy and French colonial rule bequeathed a political legacy that valued conformity, and under Diem, that adherence to a single mind-set was reinforced,” Demery writes. Even though state department and military advisors had pushed Diem for reforms and to appoint differing viewpoints to government positions, no dice. There was too much fear of those who weren’t loyal or would publicly disagree with Diem’s government. That fear made it easy for Diem to rely on his brother and Madame Nhu, since Diem lived in a cocoon from Vietnamese society.

Not everything was a slow march. Madame Nhu kept up her efforts to give Vietnamese women an active role in the war effort. She organized a unit of women trained in the use of firearms, an auxiliary ready to be called into service. In her legislative role, Madame Nhu pushed through the Morality Laws, but perhaps she went a bit too far: banning dancing, beauty contests, gambling, fortune-telling, prostitution and contraception. Madame Nhu’s stated intent was to save women by stopping exploitation, and focus her country’s attention on the war, not frivolous activities. She also felt the country’s population was too small, so it was okay to make love and war. Madame Nhu was imposing her will on the people, not unlike the government in the north.

In the early 1960s, U.S. foreign aid, military funding and tourism dollars of U.S. servicemen on leave, accounted for a hefty chunk of the South Vietnamese economy. With the aid came an increasing amount of U.S. government involvement. Diem liked the money, but not the meddling.

It is hardly a surprise that the Diem government was unpopular, both at home and abroad. The Nhus were also disliked. Demery paints a portrait of a privileged, egotistic, tone-deaf power couple. Diem and the Nhus were Catholics and found ways to anger the Buddhist population with repressive laws and treatment.

In 1962, bombs fell on the presidential palace, directly on the Nhu family suite, destroying their possessions, and killing a servant. Madame Nhu escaped with burns and minor injuries. Diem was not harmed. The writing was on the wall, but Diem and his family doubled down on ways to remain in power.

Madame Nhu had admirers, but lots of critics, particularly those who were totally confused by her increasing bold talk and criticism of her government’s allies. As her personal profile increased, she stupefied many, especially her shocking comments about the Buddhist monk who set himself on fire in protest against the Diem government. Her words were shocking, but as written in the book, that was her intent; a sort of wake-up to incredible events around them. Madame Nhu was quoted as saying “I may shock some by saying ‘I would beat such provocateurs ten times more if they wore monks robes,’ and ‘I would clap hands at seeing another monk barbecue show, for one can not be responsible for the madness of others.”

The protests continued, as did the horrendous monk suicides. The foreign media, especially in the U.S., triggered swift backlash against the Diem government. The protests turned violent and called for Diem to be removed. The U.S. had long grown tired of Madame Nhu, and had lost confidence in the Nhu brothers.

Diem declared martial law and used his secret police, wearing army uniforms, to go after the Buddhist monks, making it appear that the army did not abide by the Diem’s orders not to use force against them. Despite increasing pressure from the Kennedy administration, Diem and his brother rebuffed attempts by the U.S. to orchestrate changes.

In October 1963, Diem and his brother had organized a false coup against them, hoping it would court favor and reduce the pressure on them. Ironically, a real coup was underway by Diem’s generals. Madame Nhu and her oldest daughter happened to be away on an official visit to the U.S., when word reached them that the Nhu brothers had been arrested and killed. American complicity was charged, though not admitted at the time. Clearly, the U.S. wanted a regime change since the Diem administration, including Madame Nhu, were doing serious damage to South Vietnam’s stability and the war effort. The bodies of Diem and Nhu were horridly brutalized and paraded, a sign of the rage felt toward them.

“Whoever has the Americans as allies does not need any enemies,” Madame Nhu was quoted. She did not hide her anger at Kennedy and his administration, and claimed their involvement in the murders. The State Department had not recognized her visit as “official” and offered her no protection or housing. She also faced criticism from members of Congress, but that seemed to increase her public profile and media interest.

Madame Nhu did not return to Vietnam, although the new government sought to extradite her from France, where she lived for years, before settling in Italy near her children. It was while she lived in France that Demery connected with Madame Nhu. Over the course of several years, they talked on the telephone, sometimes often, sometimes not for long breaks. According to Demery, Madame Nhu wanted her story told, and gradually came to decide on Demery to help deliver it. Madame Nhu would eventually provide Demery with her two volume set of memoirs. Unrelated that this, Demery claims to have gotten a hold of Madame Nhu’s secret diary, which had been taken during the looting of the presidential palace after the coup, and safeguarded for years.

Finding the Dragon Lady is the culmination of many different sources of information. Demery researched the National Archives, and official records in France and Vietnam. Demery received a Master’s degree from Harvard in Asian Studies and has traveled to Vietnam. She was a co-author of They Are All My Family, the Chaos of Saigon’s Fall written with John P Riordan. This is the story of the rescue of over 100 Vietnamese civilians by banker Ralph White as the county was taken over by the communists. White wrote his own story, Getting Out of Saigon, which I reviewed.

Madame Nhu died in 2011, and Demery’s book was published two years later. The fall of Saigon was 49 years ago, two years after the U.S. withdrew troops. Why is this book even relevant? Vietnam will always be in our rear-view mirror as a set of lessons and proof that American political and military ambitions can easily descend into an expensive (billions of dollars), costly (human lives) and divisive (protests, civil unrest, election issue) clusterfuck. That’s the big reason. On a less strategic platform, Finding the Dragon Lady, is a story of mystery and fascination. Madame Nhu was despised by many important leaders, including JFK, who saw her as reckless and a significant threat. She knew how to work the media, and how to manipulate President Diem. You might not respect Madame Nhu, but you’ll acknowledge her place in history.

Leave a comment