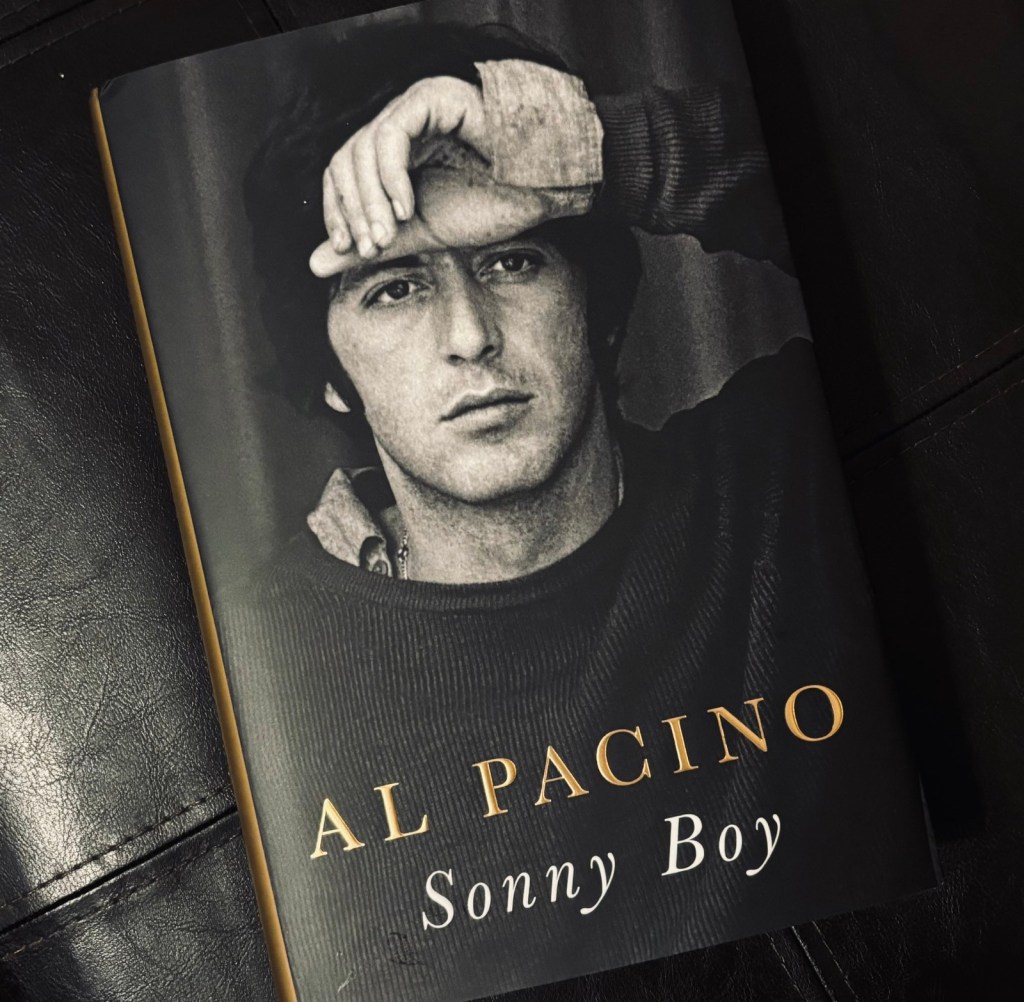

Sonny Boy. The name Al Pacino’s mother gave him. If I were to write Al Pacino’s story, I imagine his youth to be exactly how he wrote it. Nothing surprised me about his tough, younger years – poverty, lack of interest in school, discovering acting and being greatly moved, having a rebellious streak, even the departure of his father and death of his mother. All tragic, and all contributing to that intense, passionate, smoldering actor’s emotional palette.

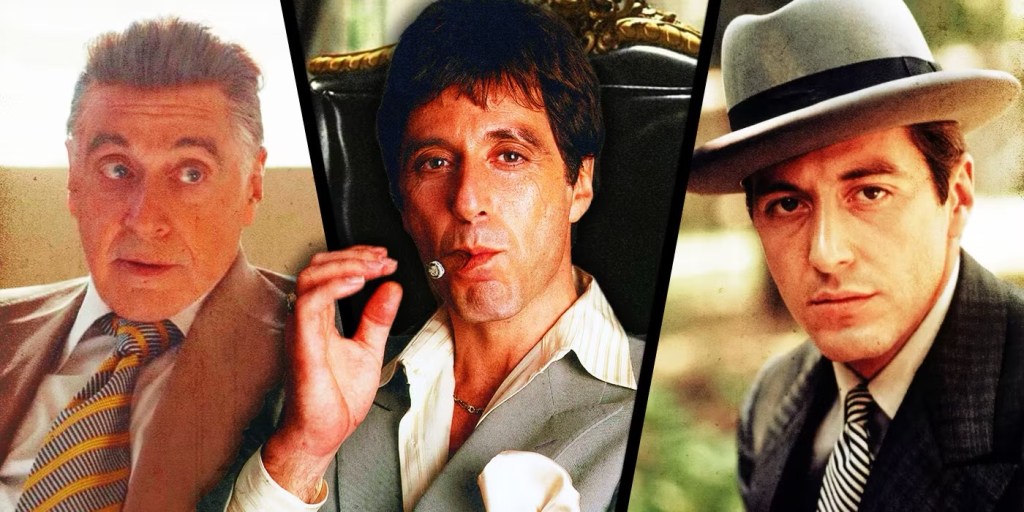

Sonny Boy (Penguin Press, 2024) is Al Pacino’s story. Poetic at times, gritty at others. It was a long haul to quality roles. A breakthrough on stage led him to film. He was a nobody until the Godfather, then everyone knew his face. He was 32 when that happened, not exactly a kid, but his boyish face gave a range of roles.

Pacino’s prospects were limited as a young boy; born to poverty, a broken family and a mother struggling with mental health issues. Instead of leaning heavily on drugs, booze, crime, loss of hope – Pacino learned to channel life into acting. Of course he did learn to medicate himself with alcohol and drugs later on, but acting was his commitment. Pacino writes that he fell in love with, and identified with, plays by Chekhov and others, finding truth in characters and situations so different from his life, yet highly relatable as an actor.

Reading Pacino’s words and storytelling adds great texture and a glimpse into why the doors eventually opened, and opened widely, for the talent waiting to find characters to portray.

For a man blessed with good looks and acting talent, Pacino struggled to feel like he deserved the intense attention; Hollywood scared him. He avoided awards ceremonies and drank to cover up his anxiety. Acting seemed easy, but success was hard.

His success on stage and on screen is less interesting (at least to me) than what made him in the first place. Movie stories, Hollywood stories, romances, fatherhood – it’s there in a somewhat abbreviated form. The interesting part of his story is how he grew into fame.

The Godfather stories are of course, required reading. Almost being fired from the film, feeling inadequate in his acting, not fulfilling director Francis Coppola’s vision for Michael Corleone – all of that swirled around in his head. Then, suddenly, it all changed with the filming of one scene. Michael Corleone kills a crooked cop and a betrayer; that put both actor and character in the game.

Pacino, like many actors, grabbed roles he liked, and tolerated roles that he needed to rescue him from insolvency, on more than one occasion. He turned down roles he couldn’t relate to (Star Wars), and guessed wrong on others (Revolution, Bobby Deerfield, Cruising).

Unlike his contemporaries Nicholson, Beatty, Redford, De Niro, Pacino was a stage actor first and foremost. That’s where he lived, even though it didn’t pay well enough to maintain the lifestyle Pacino embraced. And, he hate Los Angeles.

Pacino was beginning a career resurgence when he agreed to return as Michael Corleone in Godfather III. His most iconic role helped put needed money in his pocket, but the backlash over the film extracted a price. It was a disappointing film that seemed more of a money grab.

Pacino naturally does a lot of reflecting and soul searching in this book, time is passing quickly. He’s a father again, late in life, and his kids are his priority. Never married, he does sort of lament that none of his romances never went the distance, but he remained close to the late Jill Clayburgh, Diane Keaton and Kathleen Quinlan.

Unfortunately, Pacino does not talk about pairing with Robin Williams in Insomnia, or Russell Crowe in The Insider, or his Barry Levinson directed Paterno, or in David Mamet’s Phil Spector, or Michelle Pfeiffer in Frankie and Johnny.

Sonny Boy is not the best Hollywood memoir, but it’s far from the worst. Pacino carefully bares his soul in taking us from a poor child who loved watching movies to an actor who could have been in almost any movie.

3.75/5

Leave a comment