Don Siegel directed tough guy films, mostly. He had a long career in film, beginning as an assistant in the editing department at Warner Bros. and gradually becoming end of the department that made inserts and montages for WB films. Siegel literally went from carrying film cans to directing the biggest movie star in the world. That’s a career!

In 1993, Siegel wrote his story of his film career, A Siegel Film. Copies of his book can be difficult to find, but it’s a worthy read. Quentin Tarantino mention this book in his own book, so I did find it. Much of Siegel’s book is told as dialogue, which means he possesses an incredible memory.

While Siegel talked a lot about the films he worked on, I never got a sense of a Siegel style of filmmaking, at least not from him. Siegel directed tough loners, heroes that weren’t traditional movie heroes. His characters used as little dialogue as possible. Siegel also used that approach to his lighting, he often employed Bruce Surtees, the “Prince of Darkness” as his cinematographer. Siegel’s films were often gritty, violent and void of happy people.

What I was most interested in was his chapters on several 1960s films and his 1970s films. A nice surprise was his Warner Bros. years were quite revealing, particularly his interactions with studio head Jack Warner, and independent producer Hal B. Wallis, two of the most important and imposing individuals in Hollywood. Siegel was always very direct, even when he was a very junior employee. He knew who had the power to squash him, but that didn’t deter Siegel from standing his ground and only taking a minimum of shit.

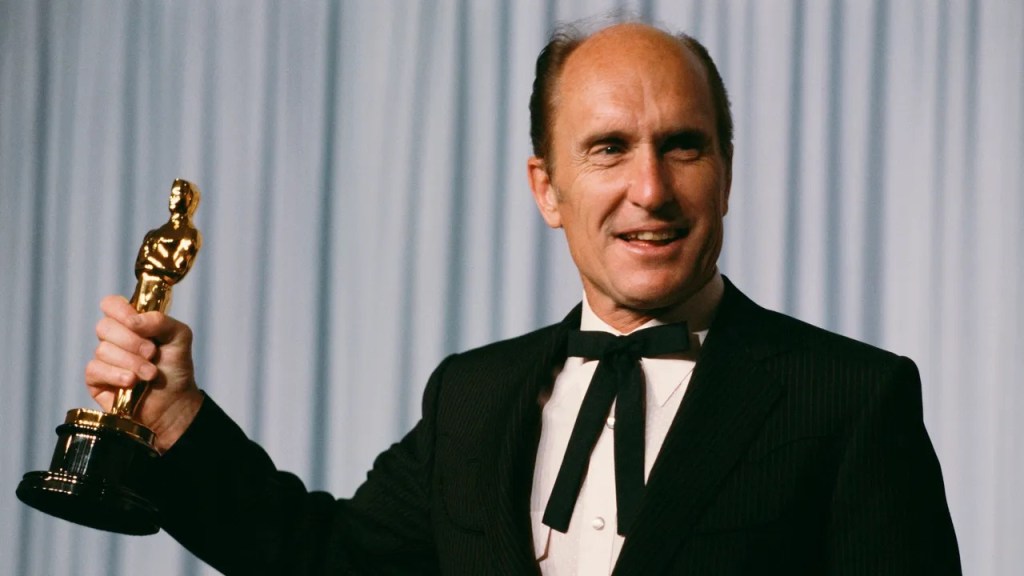

Siegel went on suspension, and would refuse to sign lousy contracts. He knew his own talent and what he had accomplished. On his journey to becoming a director, Siegel would threaten to leave WB, and direct two short films, each of which earned the studio an Academy Award.

—

In the 1950s, Siegel directed whatever he was offered, usually b-films, with a couple of them standing out. Riot in Cell Block 11 (1954) and Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956). Both had great stories and a cast of tremendous character actors. Siegel got the most of what he had to work with, and his background in editing was invaluable.

Sometimes he found the assignment near impossible. Siegel agreed to direct The Gun Runners for Clarence Green, a former boxer. The film was a remake of a remake, but without the star power or smart dialogue of either. Here was Siegel’s conversation as he remembered it:

SIEGEL: Great. I’d like you to hire Danny Mainwaring for the rewrite. He’s gotten me out of similar messes.

GREEN: I’ll set up an appointment to see him.

SIEGEL: Why not send him a script immediately? I’m sure he’s seen the two better versions, as have most movie-goers. Before I leave, I want to level with you. I’m amazed that you want to do a remake of a remake. Why not do an original story?

GREEN: (A bit miffed) My instincts tell me to do the third version.

SIEGEL: Your instincts will win because you’re the producer. I hope I’m wrong, but in the end, you’ll lose. (As I start to leave, I turn back.)

SIEGEL: Who do I have to fuck to get off this picture?

—

One of the things I got from Siegel is that most Hollywood people in power are rude, assholes on the job, including Siegel. He writes of two members of his crew were targeted for his abuse. They were proving stunts in a film involving a getaway car in a robbery and is involved in several crashes, but keeps going. Dangerous stuff. Here is what he writes:

SIEGEL: (To Whitey) I have a pretty good idea of what you must think of directors. I spent seven years in special effects at Warners and, without a doubt, you are the most incompetent head special-effects man I’ve ever had the displeasure of working with.

Why would be write that in his book, it’s not flattering. He could have just describe the challenge without putting in writing how he spoke to his employee. Siegel provides quotes from studio executives and producers who didn’t think much of his work or problems that arose. You must need a thick skin to survive in that world.

—

Siegel’s stories are quite entertaining. He was requested by Jack Warner to help Howard Hughes save a film in the editing room. His meetings with Hughes are interesting to see the least.

“The next morning, I wrote him a three-page memo of what I hoped would be construed as constructive comments. At the end of the letter, 1 couldn’t stop myself from adding: ‘Whether, Mr Hughes, you have read this far in this letter is unimportant. Nothing can save Vendetta.’ I sent the letter off to Hughes with a copy to Jack Warner.”

Jack Warner is a frequent character in Siegel’s book. As head of the studio, Warner seemed involved in every detail on the lot, and he and Siegel bumped heads often. As the person putting together montage sequences for Warner Bros. films, Siegel thought up ways to bring attention to them, without spending any more of Jack Warner’s money.

“For one, I found five camels, took their picture in dozens of poses, printed the pictures, cut them out and mounted them on a camshaft to have them move. Then I set up a scene with Fredric March projected on a miniature screen on a miniature minaret. As the camera pulled back, it picked up the camels and came through a cut-out crowd of Arabs – it looked as though there were thousands of them. The camera stopped at two of the five real actors, who turned to each other and laughed at Mark Twain’s joke. When Jack Warner saw the sequence he blew his stack. He thought hundreds of extras had been hired and he blamed me for wasting a fortune.”

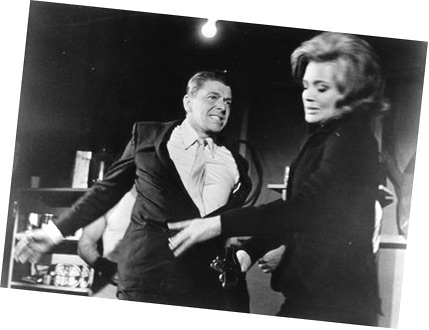

Siegel was making a new version of The Killers based on a Hemingway story. Actually, only the title was used, the best was newly written. In casting the film, Siegel took a run at Ronald Reagan to play the top bad guy, who even slaps Angie Dickinson in the film. Reagan’s acting career was about done, but he had never played a villain on screen. Thankfully, he dies in the end.

Siegel directed John Wayne’s last film, The Shootist. Wayne was quite ill and that made for problems, including the film being shutdown. Wayne, like Eastwood, exercised a lot of control over the production. Siegel also had to deal with Wayne’s tendency to take over direction.

—

Dirty Harry really set Siegel up for the rest of his career, although he signed on for a couple of dogs (his choice). Siegel was usually the director and producer, but he didn’t handle stuff like negotiations and other administrative headaches.

Siegel and Eastwood made five films together, they were both helpful to the other’s career. The making of Dirty Harry and Escape From Alcatraz are two of Siegel’s best stories. Made seven years apart, they represent different things to Siegel, who was nearing career end, and Eastwood, who was now the biggest movie star in the world.

Most people don’t know about Don Siegel, but have watched his films, or watched the films of the many filmmakers he directly influenced.

Siegel films:

Star in the Night (1945 short)

Hitler Lives (1945 documentary short, uncredited)

The Verdict (1946)

Night Unto Night (1949)

The Big Steal (1949)

The Duel at Silver Creek (1952)

No Time for Flowers (1952)

Count the Hours (1953)

China Venture (1953)

Riot in Cell Block 11 (1954)

Private Hell 36 (1954)

The Blue and Gold (1955)

Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956)

Crime in the Streets (1956)

Baby Face Nelson (1957)

Spanish Affair (1957)

The Gun Runners (1958)

The Lineup (1958)

Hound-Dog Man (1959)

Edge of Eternity (1959) – Man at Motel Pool (uncredited)

Flaming Star (1960)

Hell Is for Heroes (1962)

The Killers (1964)

The Hanged Man (1964)

Stranger on the Run (1967)

Coogan’s Bluff (1968)

Madigan (1968)

Death of a Gunfighter (credited as Alan Smithee) (1969)

Two Mules for Sister Sara (1970)

The Beguiled (1971)

Dirty Harry (1971)

Charley Varrick (1973)

The Black Windmill (1974)

The Shootist (1976)

Telefon (1977)

Escape from Alcatraz (1979)

Rough Cut (1980)

Jinxed! (1982)

Leave a comment